feature / alumni / transportation-design

October 25, 2015

Writer: Sylvia Sukop

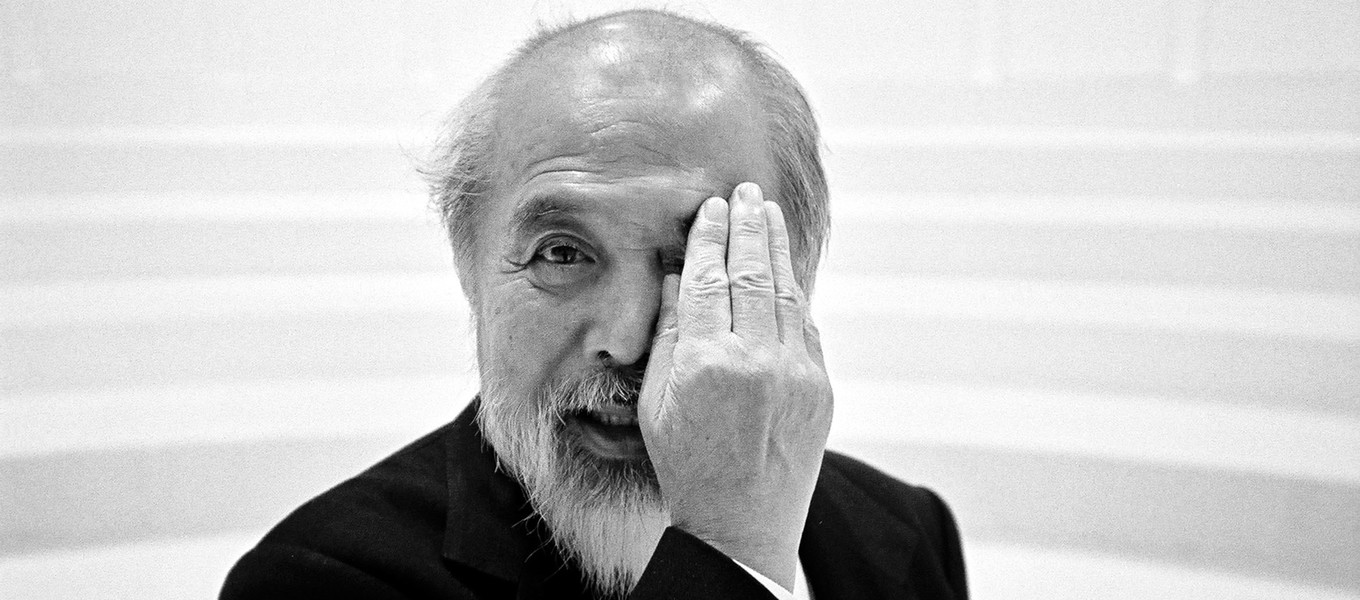

Remembering Kenji Ekuan

Kenji Ekuan’s singular career began with a singular event—the destruction of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

A teenager away at a naval academy when an American B-29 dropped the atomic bomb on his hometown, Ekuan survived, but he witnessed the aftermath firsthand. His sister was killed in the blast and, a year on, his father died of radiation sickness.

The devastating sight of “nothing”—the literal loss of every “thing”—changed Ekuan forever. He decided then to become a maker of things. And throughout his long and influential career, the things he made became icons of contemporary design.

“Mr. Ekuan simply loved design,” says Norman Kerechuk (BS 85 Transportation Design), president of GK Design International Inc. “He believed design had no limit in its ability to solve human problems, and he made design his sole mission in life.” Kerechuk joined Ekuan’s company in 1987, and has spearheaded an ArtCenter scholarship in honor of his longtime friend and mentor.

Thoughts soaring high in the sky, a single blossom.

Kenji Ekuan (1929–2015)

Before coming to ArtCenter, graduating in 1957 among its first group of Japanese students, Ekuan had trained to become a Buddhist monk, following in the footsteps of his father who oversaw a temple in Hiroshima. Although Ekuan endured the city’s destruction and Japan’s subsequent occupation by United States armed forces, he never spoke bitterly about either event, says Kerechuk. “He only spoke about his inspiration to help his country recover and restore normal life for the people.”

A pioneer throughout the formative years of the industrial design profession, and its tireless global ambassador, Ekuan’s legacy includes 13 design offices in four countries, a family of companies known as GK Design Group; a multitude of design awards including the prestigious International Compasso d’Oro (2014); and scores of published books and articles. He remained active in ArtCenter’s alumni network till the end of his life.

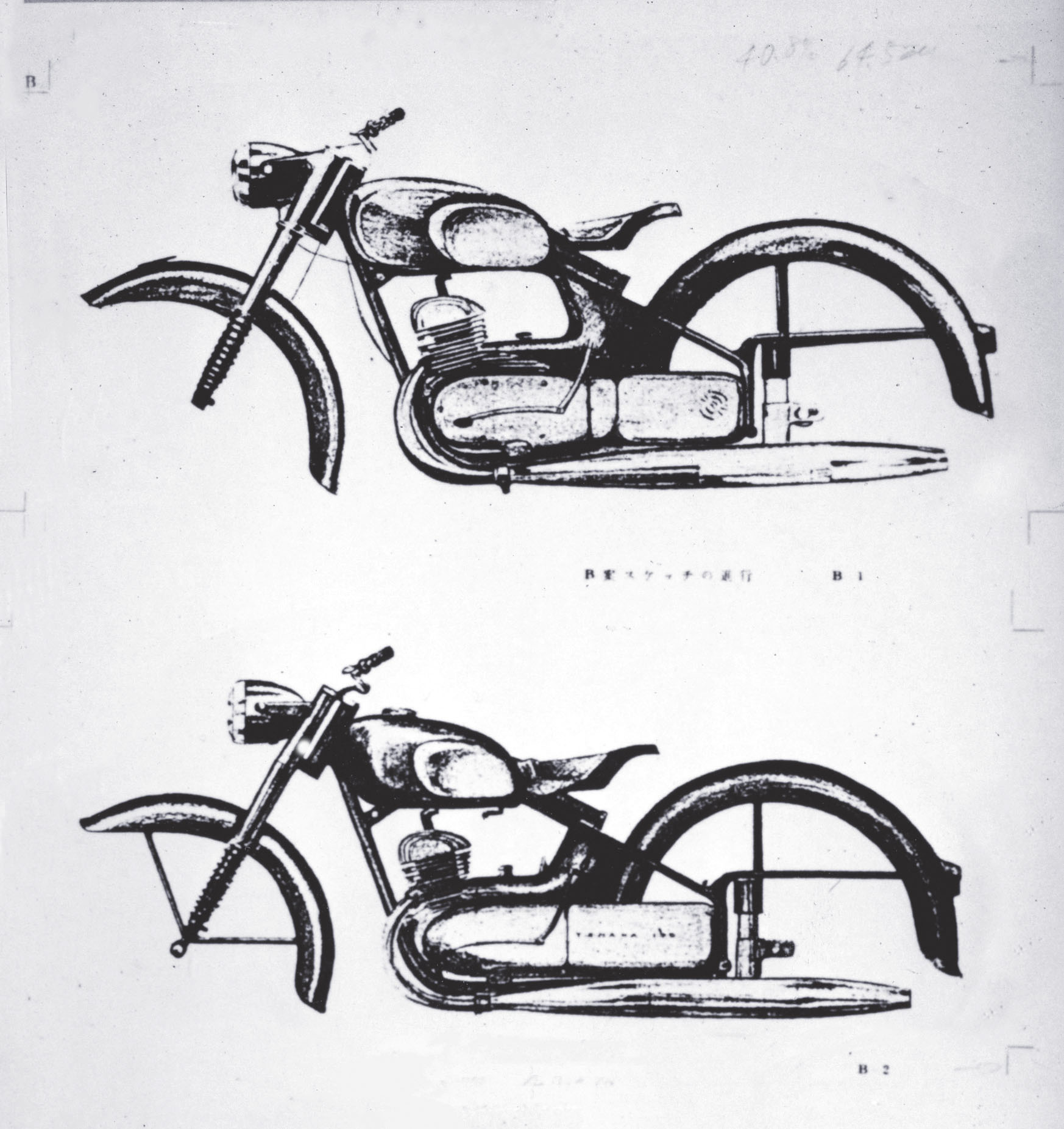

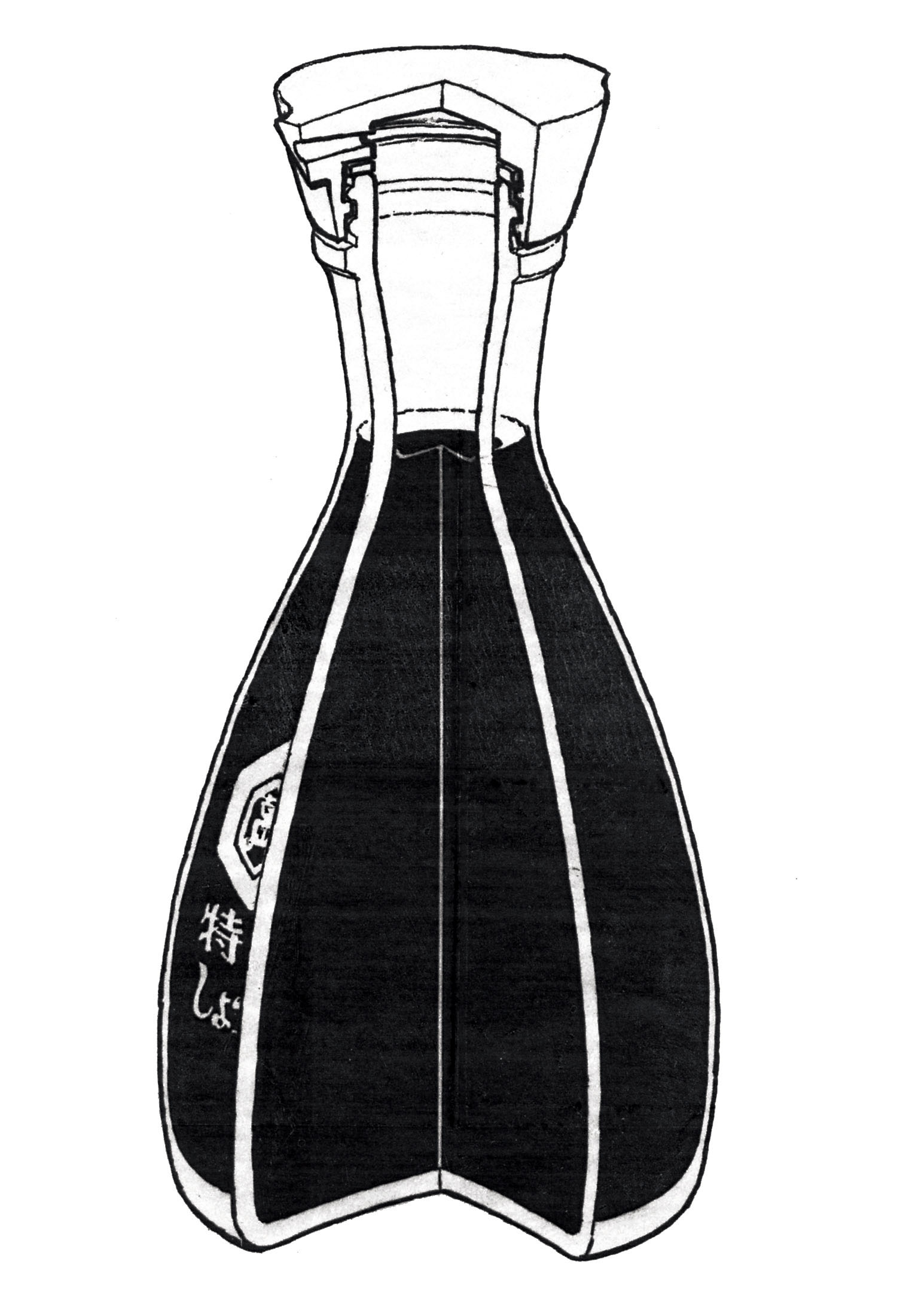

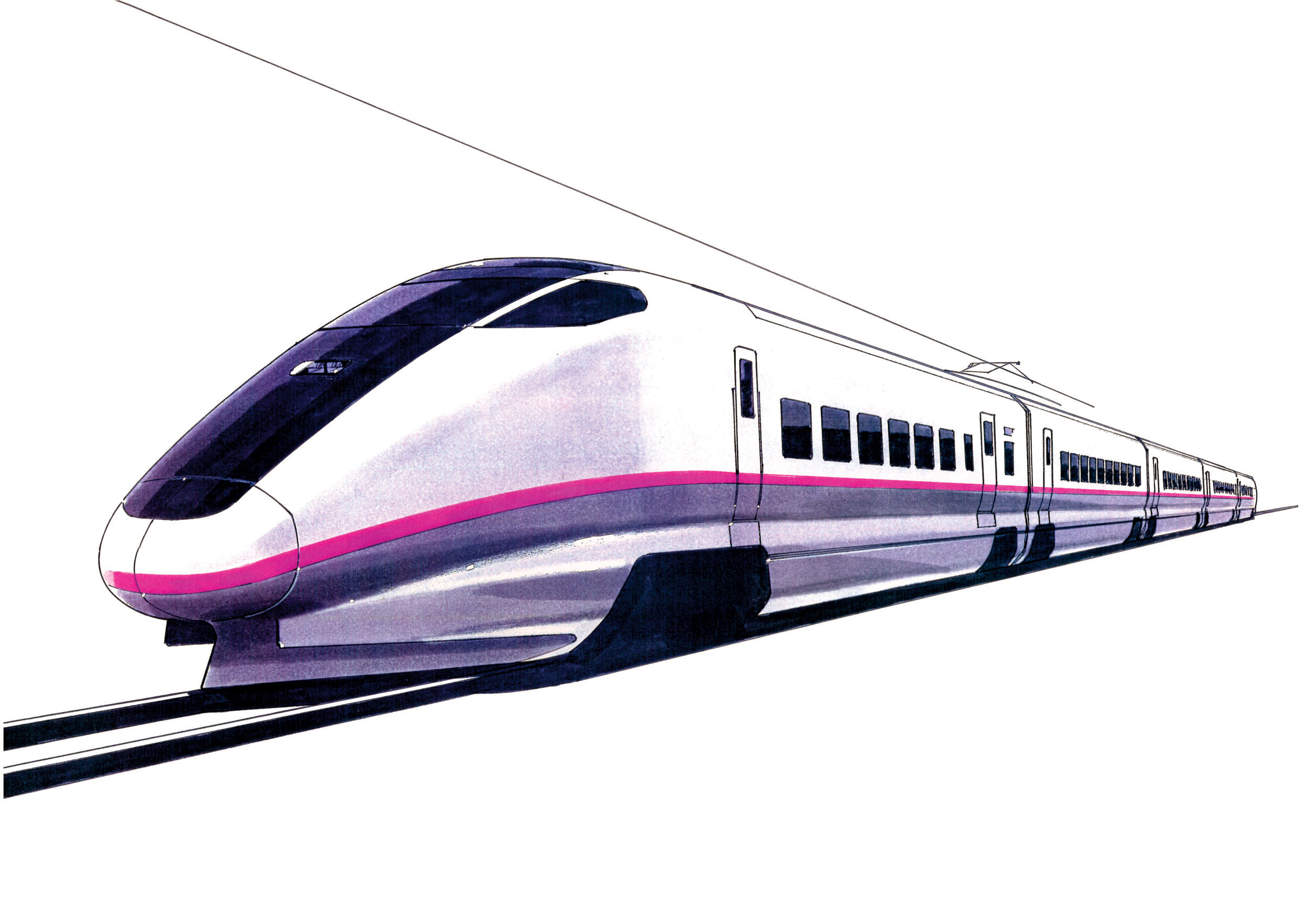

Among Ekuan’s final projects: taking his retrospective exhibition Soaring High in the Sky to Hiroshima in 2014. Closing just two months before his death, it showcased many of his renowned products of utility, spanning six decades. But it also featured some of his more metaphysical creations, Ekuan’s vision of utopia, for example: A minimalist golden carriage carries a “heavenly maiden” amid a fragrant sea of blue lotus flowers, resting in the eternal flow of time.

Related

impact-90-300