feature / alumni / film / photography-and-imaging

May 13, 2019

By Matthew Rolston

Icon Worship

Photographer and alum Matthew Rolston Leads Tour through the Getty Museum’s Icons of Style Exhibition

This past September, Matthew Rolston—a photographer and director who has created countless iconic portraits of celebrities including Madonna, Jay Z, Lady Gaga and Taylor Swift for publications like Vogue, Vanity Fair, Harper’s Bazaar and Rolling Stone—led a small private tour of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s exhibition Icons of Style: A Century of Fashion Photography, 1911-2011 for members of the ArtCenter community.

The exhibition, which closed in October, was touted by the Getty as “the most comprehensive exploration of this phenomenon yet undertaken.” It featured more than 160 fashion photographs as well as a collection of costumes, illustrations, magazine covers, videos and advertisements.

(Photo by Ross LaManna)

Among the ArtCenter luminaries in attendance were President Lorne Buchman, Photography and Imaging Chair Dennis Keeley, and Film Chair Ross LaManna. An alumnus of and also an instructor at the College, Rolston studied under both the Film and the Photography and Imaging departments while at ArtCenter. He is also a lifelong fan of fashion and magazine photography—a topic of which he knows a fair amount.

(Photo by Ross LaManna)

Icons of Style was organized by Paul Martineau, the Getty Museum’s associate curator in the department of photographs and a significant historian in the area of photographic imaging. Martineau later joined the group to sign copies of the exhibition’s catalogue and to answer questions.

Below are edited excerpts from Rolston’s lecture and tour, which concentrated on a small portion of the images in this landmark exhibition.

MATTHEW ROLSTON: Why is this exhibition important? Well, before I begin to answer that I’d like to say that these are my own personal views of the work, they are entirely subjective and, given our time constraints and the scope of this exhibition, I can only touch lightly on the subject.

You’re going to notice a number of repetitive threads in my comments today, and that’s because fashion and fashion photography themselves are cyclical. The ideas build upon what came before. And truthfully, the world of fashion photography is made up of a small and rarefied group of people who all tend to influence one another.

My comments are not necessarily reflective of the Getty curator’s point of view. Not that I disagree with anything Paul Martineau has done here. Far from it. It’s just that I’m not here representing him.

This exhibition is important to me because I think of fashion photography as an art movement, an “ism.” For example, there was Impressionism, there was Surrealism, and to my mind, there is “Fashionism,” which is a term I might have invented (laughs). And Fashionism may in fact be drawing to a close.

We are now at an inflection point with fashion photography. Clearly, we've arrived at a time where a new generation is primarily consuming media on mobile devices, not on the printed page, and the nature of that digital experience is just different. And if you go with my theory that Fashionism is an art movement that is coming to an end, it's because we are witnessing the demise of the traditional magazine as a form of media, and therefore the demise of the still image in printed form.

The interest in fashion and fashion imagery isn’t going away, but its future seems split into a couple of directions. Number one is the miracle—and perhaps scourge—of digital disruption. Everyone is a photographer because everyone has a fabulous camera right in their hands. There’s literally no barrier to entry. That doesn’t mean everyone can make a great photograph on a conceptual level, but everyone can make a great photograph on a technical level.

So, one future of the fashion image will be social media. Seflies, Instagram, the gamut. Power to the people.

Number two is the previously mentioned demise of printed media, and thereby the shift from stills to the moving image, which has given rise to a new form known as the ‘fashion film.’ It’s a huge shift for the next generation, and as much of a game-changer as MTV and music videos were for mine. Fashion films and social media have and will continue to replace fashion’s still images, soon to be followed by advances in immersive entertainment.

Perhaps this new movement can be termed “Post-Fashionism.” After all, we’ve had Post-Impressionism, haven’t we? And that is yet one more reason I think Icons of Style is so timely and so important.

The history of fashion photography lives in the rooms of this exhibition. The story begins in the early 1900s, and this particular narrative ends in 2011—100 years of fashion photography.

When I first saw the show, I had the odd impression of physically entering into my own subconscious because, throughout my life, I've studied these pictures over and over; they’re like friends to me (and, thanks to Paul Martineau, there are a few wonderful surprises that I'd never seen before).

In terms of context, it’s important to consider that fashion itself, fashion imagery, fashion magazines, fashion photographers, fashion editors, and the history of women in our culture are inextricably intertwined.

And that is yet one more reason why Icons of Style has such cultural resonance for me.

1911–1919

Okay, let’s begin at the beginning. Around 1900, fashion photography was born, with the creation of the first “artistic” fashion photograph. What exactly qualifies an image as an “artistic” fashion photograph? To be clear, there had been photographs of fashion in magazines before this moment of prominent women—influencers of their day—wearing the latest designs and photographed in a kind of “false-documentary” style.

Fashionable women were often pictured attending the races or other exclusive events, but in reality, these appearances were planned, as can be seen in the photograph La mode aux courses, Longchamps (Fashion at the races, Longchamps), created in 1909 by Séeberger Frères. The image was featured on the cover of Longchamps, an early fashion magazine. These icons of style were not models by trade, but rather were paid to wear the gowns in the photographs or perhaps compensated with clothing.

(Image courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Sounds a little like today’s ‘influencers,’ doesn’t it?

An “artistic” fashion photograph was a significant innovation at the time. It was a highly expressive interpretation of fashion. Not a document. Not a record, however false, of an event. The artistic fashion photograph’s intent was evident: to create art out of fashion, in exactly the same way that fashion illustration worked at that time. Illustration was the dominant form of expressive fashion imagery until the advent of this new form.

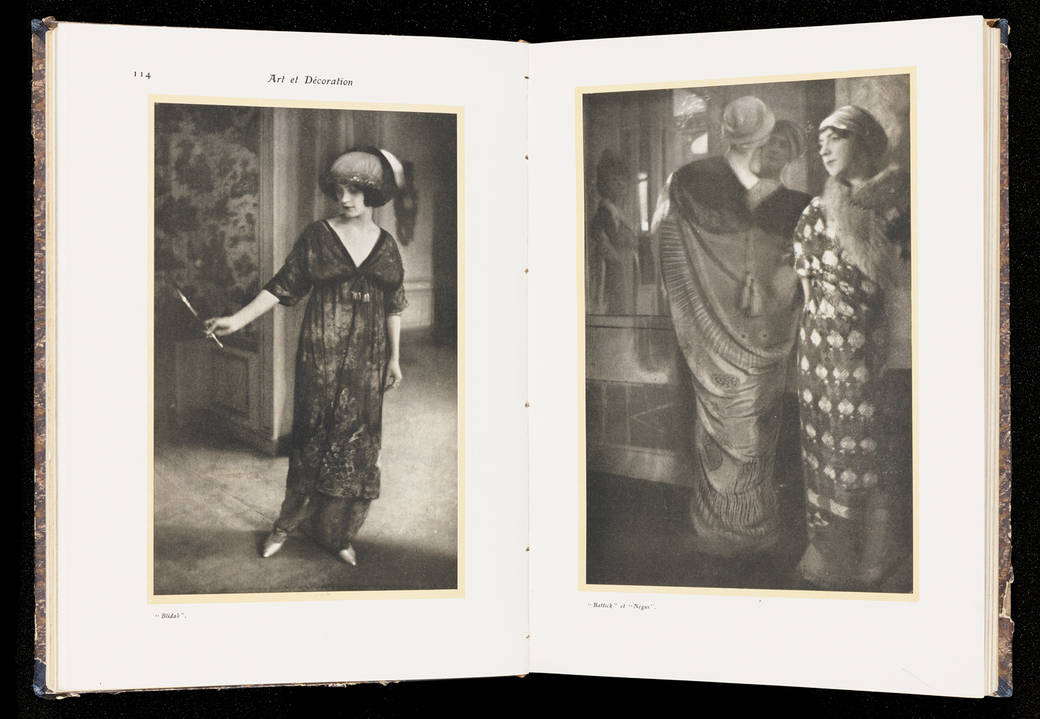

The American painter (and later photographer) Edward Steichen is credited with the creation of the very first “artistic” fashion photograph. In “Blidah” Dress by Paul Poiret, we can see an early example of Steichen’s fashion photography, created in 1911 and depicting a gown by Parisian designer Paul Poiret. Utilizing his extensive knowledge of drawing and painting, Steichen authored a style of photography that was known as Pictorialism, which used various techniques to mimic the look and feel of painting.

In 1913, the renowned photographer Baron Adolf de Meyer made a portrait of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, who was a prominent New York socialite, art patroness, and a fashion avatar of the period. Titled Mrs. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, in a Costume by Léon Bakst, the photograph exploits an elite point of view about style, one that was also at play then in the worlds of art, theater, and music.

That style was called Orientalism—various Asian motifs as seen through Western eyes. Think of the Orientalism fashion of the early years of the new century as a reaction against Victorianism’s often-xenophobic culture—and its prudish attitudes about sensuality and female freedom.

De Meyer went on to become one of the leading fashion photographers in the world over the next 20 years, commissioned by none other than Condé Nast himself, who published Vogue and Vanity Fair magazines, and later at Harper’s Bazaar, which was published by William Randolph Hearst. This particular image has been identified as the very first commissioned fashion photograph for Condé Nast publications. The two true pioneers of fashion photography were Edward Steichen and Baron de Meyer.

1920–1929

Throughout the 1920s, the dominant figures in fashion photography remained Edward Steichen and Baron de Meyer, but towards the end of the '20s, fashion underwent an extraordinary change. Orientalism and over-the-top extravagance were out. Modernism was on the way in.

Designers raised hemlines and dropped waistlines, and a slender, somewhat-androgynous look became the rage as the jazz age arrived. Young women defied convention by bobbing their hair, leaving corsets and other stifling forms of dress behind—they smoked in public—and the image of the modern independent woman was born.

(Image courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

In Photo Shoot with Beachwear by Schiaparelli, made in 1928 by Russian-born, Paris-based photographer George Hoyningen-Huene, male and female models, both smoking cigarettes, wear bathing costumes by the Italian-born, Paris-based designer Elsa Schiaparelli (who was a contemporary of Coco Chanel). This photograph perfectly encapsulates the new rhythms of the jazz age; the forms in this image are positively syncopated.

A new conceptual idea had emerged. For the first time in fashion photography, there was a conscious blurring of gender display—an androgyny that was extremely daring for the time, and a marker of the freedom-of-thought for the elite of that period.

Hoyningen-Huene’s image ushered in modernism in many ways, but then came the stock market crash of 1929, and the world was forced to grapple with a grim new reality..

1930–1939

Beginning in 1930, the elite—not to mention the rest of humanity—lost the freedom that was so rife in the jazz age. Attitudes shifted. There was a desire to return to more comforting depictions of traditional femininity, and a renewed hunger for escapism given the terrible realities everyone was facing during the Great Depression.

And like any period, there were trends, one of which was a turn towards goddess imagery. There was now a move in fashion to create an association between the modern and the antique.

Miss Sonia, Pajamas by Vionnet, Paris, 1931, is another fine example of the photography of George Hoyningen-Huene—but how very different from his jazz age presentations.

This photograph resembles a Greek bas-relief, as if on a temple—perhaps one dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite—and portrays a persuasive view of traditional feminine power.

(Image courtesy of Stiftung F.C. Gundlach, Hamburg)

Gone was the assumption of androgyny and its associated new freedoms, and at least here, in its place, was the epitome of traditional feminine grace. My, how times had changed.

There’s another manipulation at work here. In 1931, photographic technology did not allow for the freezing of motion, so there is no real movement captured in this image. It is actually posed. The photograph was made with the model lying down on a slanted board covered in black velvet and shot from above. The model’s gestures mimic those of a Greek temple dancer. The folds of the fabric of her gown, while immobile, had been carefully arranged to appear as if in motion.

Consider that method of portraying movement in a photograph versus the important innovation of Jumping a Puddle, created in 1934 by a Berlin-based, Hungarian photojournalist named Martin Munkácsi, just a few years later than Hoyningen-Huene’s goddess. This photograph is worlds apart in its portrayal of, among other things, motion. Before Munkácsi, there had been no fashion photographs of women in actual movement. None at all. But progress in photographic technology had led to faster film stocks and the adoption of the roll film camera—as opposed to single plates—which made all the difference.

The new technology emerged, perhaps quite naturally, in the world of sports photography, especially in the portrayal of athletes in motion, and Munkácsi was one of the first practitioners of this technique.

© Estate of Martin Munkácsi, Courtesy Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

At the time, Carmel Snow was the editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar. Snow was one of the most forward-thinking fashion people of her era, and her point of view was international in scope. Snow’s ideas, although not particularly well-sung today, have been handed down and continue to influence the course of modern fashion imagery. It’s important to remember that Carmel Snow was the person who ‘discovered’ the legendary French-born fashion editor Diana Vreeland, as well as Russian-born seminal art director and the Bazaar’s chief designer Alexey Brodovich, not to mention the most successful fashion and portrait photographer of the 20th century, American-born Richard Avedon. She also gave Frenchman Christian Dior his first job as a sketch artist for Harper’s Bazaar, long before she celebrated him as a fashion designer.

But perhaps Snow’s most meaningful innovation was to put the modern woman in movement. Real movement—perhaps staged—but not posed. Carmel Snow helped give birth to the first photographically liberated woman.

Towards the end of the 1930s, World War II shook the globe. The effects of the war on the progression of fashion photography and imaging of women were far more deeply felt than those of the Great Depression.

1940-1949

As the '30s drew to a close, fantasy in fashion was lost. That old shadowy glamour, its mystery, its allure, had no place in a world where women needed to take on important new roles for the war effort. Many of the men were gone, and women took their place in the workforce.

Paris fashion virtually closed down during the Nazi occupation. The focus of fashion, at least for Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar, the dominant style publications, turned to New York. Wartime rationing and new roles for women led to new trends in fashion that purposefully employed considerably less fabric, resulting in shorter skirts and tight tailoring. Women’s new place in society resulted in mannish clothing featuring heavily-shouldered suit-type jackets. For quite a few years, this was “the look.”

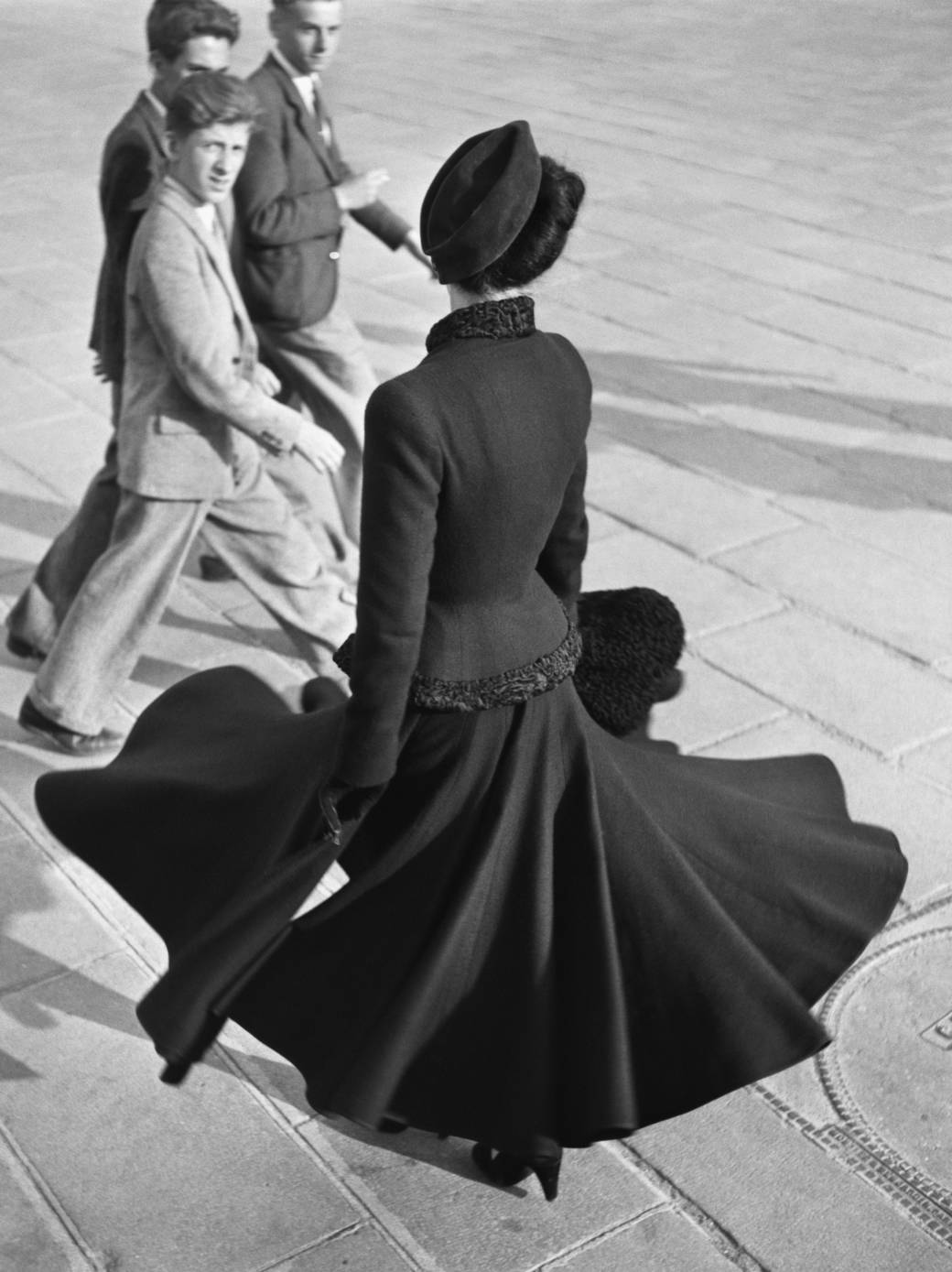

But by the end of the '40s, and the end of the war, Paris fashion miraculously returned to life, and nowhere more so than at the hands of couturier Christian Dior. Remember, Carmel Snow had given Monsieur Dior his first chance to be published (as a sketch artist in the Bazaar). And now, Mrs. Snow rediscovered Monsieur Dior and crowned him the king of Parisian couture, supposedly dubbing his 1947 collection “the New Look.” Snow’s exact words were, “It's quite a revolution, dear Christian! Your dresses have such a new look!"

Renée, the New Look of Dior, Place de la Concorde, Paris, August 1947, by Richard Avedon, ushered in the rebirth of haute couture and signaled the end of the World War II period of austerity. It was clearly a conscious homage by Avedon to the work of Munkácsi in its use of staged yet seemingly spontaneous movement. But what caught the eye more than anything was the voluminous amount of fabric in the long skirt—rich fabric, which no longer needed to be rationed.

Photograph by Richard Avedon

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Dior’s designs, this particular photograph and its subsequent publication in the Bazaar under the direction of Carmel Snow have together been credited with virtually reviving the French luxury textile and fashion industries after the War.

1950–1959

Many style experts consider the 1950s to be the golden age of fashion and fashion photography, and there is one image from that period which seems by general agreement to stand head and shoulders above all other American fashion photographs from any era.

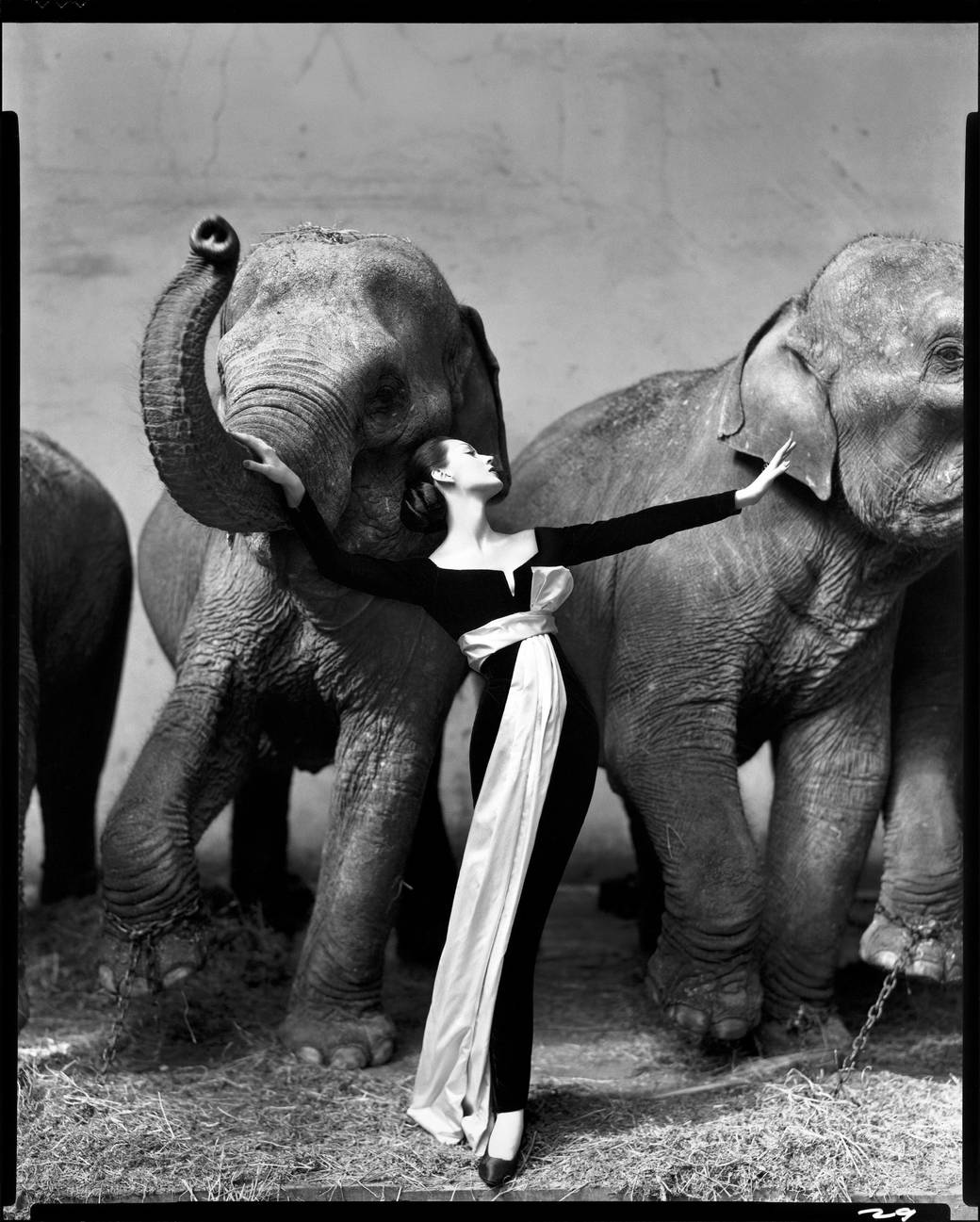

Dovima with Elephants, Evening Dress by Dior, Cirque d’Hiver, Paris, August 1955 is widely thought to be the masterpiece of 20th-century fashion photography. It has the distinction of being sold for the highest price of any fashion photograph in history. If one was lucky enough to acquire a vintage print today, it would cost upwards of $1.5 million for a single print.

The work was made by the great Richard Avedon, here once again commissioned by Harper’s Bazaar editor Carmel Snow.

Photograph by Richard Avedon

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Let’s examine the image from a conceptual standpoint, in this case, a dialectic construct referred to as the “unity of opposites.”

The unity of opposites is a fairly simple idea that states that nothing in the human experience can be described without also describing that which it is not. Every “thing” is equally the “anti-thing.” There’s no tall without short. There’s no light without dark. Think about it: Darkness and brightness are both qualities of light. They are light.

And that concept of contradiction is very much a guiding force behind the most powerful and memorable designs in the worlds of fashion, fashion imaging, and general communication. This was understood by Carmel Snow and her colleagues. It was Snow who helped put the unity of opposites into play in the world of fashion.

The contradictions inherent in the unity of opposites as an aesthetic theory create a mental state for the viewer that’s known as “cognitive dissonance.” It’s not easy for us to consider two opposing ideas at the same time—that’s what cognitive dissonance refers to—but, under the correct cirumstance, that dissonance can also provide a very specific kind of pleasure to an audience.

Take horror films for example. Yes, there’s a feeling of danger, but we enjoy being scared under the right conditions, such as the perceived safety of a movie theater. Another contradiction is that you feel frightened, and at the same time, there’s a kind of erotic thrill. That’s why the ‘thriller' makes such an enjoyable date night for young people.

With this Avedon photograph, which in my opinion was conceptually born from points of view advanced by the brilliant Carmel Snow, we have quite a few contradictions and, importantly, the special conditions here are the heady admixture of cognitive dissonance and high style.

Consider the following contradictions at play in Avedon’s image: human civilization versus animal wildness; the smooth versus the rough; the appearance of freedom versus literal imprisonment (the animal is in chains, after all) – we could go on and on.

Perhaps that’s why this photograph has proven to be so powerful for generations of viewers.

1960–1969

The 1960s were a time of enormous change. As the '50s came to a close, Carmel Snow entered retirement and was replaced by her protégée, Diana Vreeland, who now took her place as the dominant editorial voice in the world of fashion.

It’s interesting to note that Vreeland seems to have received the lion’s share of history’s credit for setting the spirit of the fashion media world we know today, but as mentioned earlier, she began as a discovery and disciple of Mrs. Snow. Vreeland took Mrs. Snow’s ideas a good deal further; she was exceptionally attuned to the social climate of her time. Vreeland didn’t just reflect that climate, she actually helped create it. She didn’t believe in giving people what they wanted, she strived to give people what “they didn’t know they wanted.”

Later in the decade, Vreeland was stolen away from the Bazaar and became the editor-in-chief of American Vogue. And in so doing, the locus of fashion power drifted away from Hearst publications, and from that day until today, American Vogue became the world’s dominant fashion publication, not Harper’s Bazaar.

Vreeland continued to work with many of the greats of the '40s and '50s, in particular Richard Avedon, but she also discovered a whole new world of fashion talent in design, photography and models. For example, it is Vreeland who is credited with discovering models Suzy Parker, Twiggy and Veruschka, among a raft of others. Significantly, Vreeland was the first editor to put a non-Caucasian on the cover of Vogue.

A Vogue Paris cover image, Veruschka in Yves Saint Laurent Safari Jacket, photographed in 1968 by Franco Rubartelli (who got his start with Vreeland at American Vogue) has become known as both an iconic fashion photograph and a harbinger of its time for a number of reasons.

To begin, the Jet Age had well and truly arrived, and it was par for the course to travel to exotic locations to shoot fashion. Secondly, think of the times: In May 1968, there were major student uprisings in Paris, protesting the war in Vietnam, France’s presence in Algeria (among many other things), and exerting the power of a new generation. The old guard was out, the Rive Gauche was in. And no one encapsulated those feelings in fashion more powerfully than the designer Yves Saint Laurent.

So here we have an empowered woman—no less than the Amazonian Veruschka, her legs planted firmly apart, somewhere in the desert (perhaps suggesting Algeria), flaunting her sexuality and casually toting a rifle—on the cover of Vogue Paris. It was “fashion at the barricades,” and clearly an overt reference to the events of May '68 in Paris. And undoubtedly, this image served as a precursor to women’s liberation, a political movement that would exert immense cultural influence just a few years later.

(Image courtesy Ira Stehmann Fine Art, Munich)

Before we move on from the '60s, let’s examine another influential moment in the career of Richard Avedon: his photograph entitled China Machado, Evening Pajamas by Galitzine, London, 1965.

By the beginning of the '60s, Avedon began to develop a new, more minimalist style, and here we can see its mature form in a spirited fashion image of model China Machado. Machado was a woman of Chinese and Portuguese descent and, notably, she was the first model of color to appear in Harper’s Bazaar back in 1959 (also photographed by Avedon).

Photograph by Richard Avedon

© The Richard Avedon Foundation

Hearst’s senior editors at first refused to publish the photograph, reportedly because they found Machado’s appearance to be “insufficiently Caucasian,” until Avedon threatened to cancel his contract with the Bazaar entirely. Importantly, this marked another move forward by Avedon in his personal quest to diversify the cultural depiction of women and portray people of color in fashion media.

1970–1979

In the 1970s, a number of seismic shifts took place in media and society. Among those shifts, importantly for fashion photography—which is, after all, consumed with imagery of women—was the advent of the women’s liberation movement. This movement occurred with a level of force that hadn’t been seen since women’s suffrage during the late 19th century. Women were empowering themselves, seeking agency in society at large. Traditional gender roles were strongly challenged.

In 1971, Diana Vreeland was forced to retire from the editorship of Vogue. The publishers of the magazine felt that her previously prescient attitudes had now become out of touch with the modern woman. Vreeland’s overheated visions of fantasy and rebellion were out. A new reality was in. It was the era of the working woman. Vreeland, missing that new wave, allowed Vogue’s newsstand and advertising sales to dip dangerously low towards the end of the '60s. By '71 she was relieved of her duties.

Replacing her as editor-in-chief was the avatar of the '70s working woman, Grace Mirabella. Fantasy of the old school was done. But fantasy itself wasn’t over. It had changed.

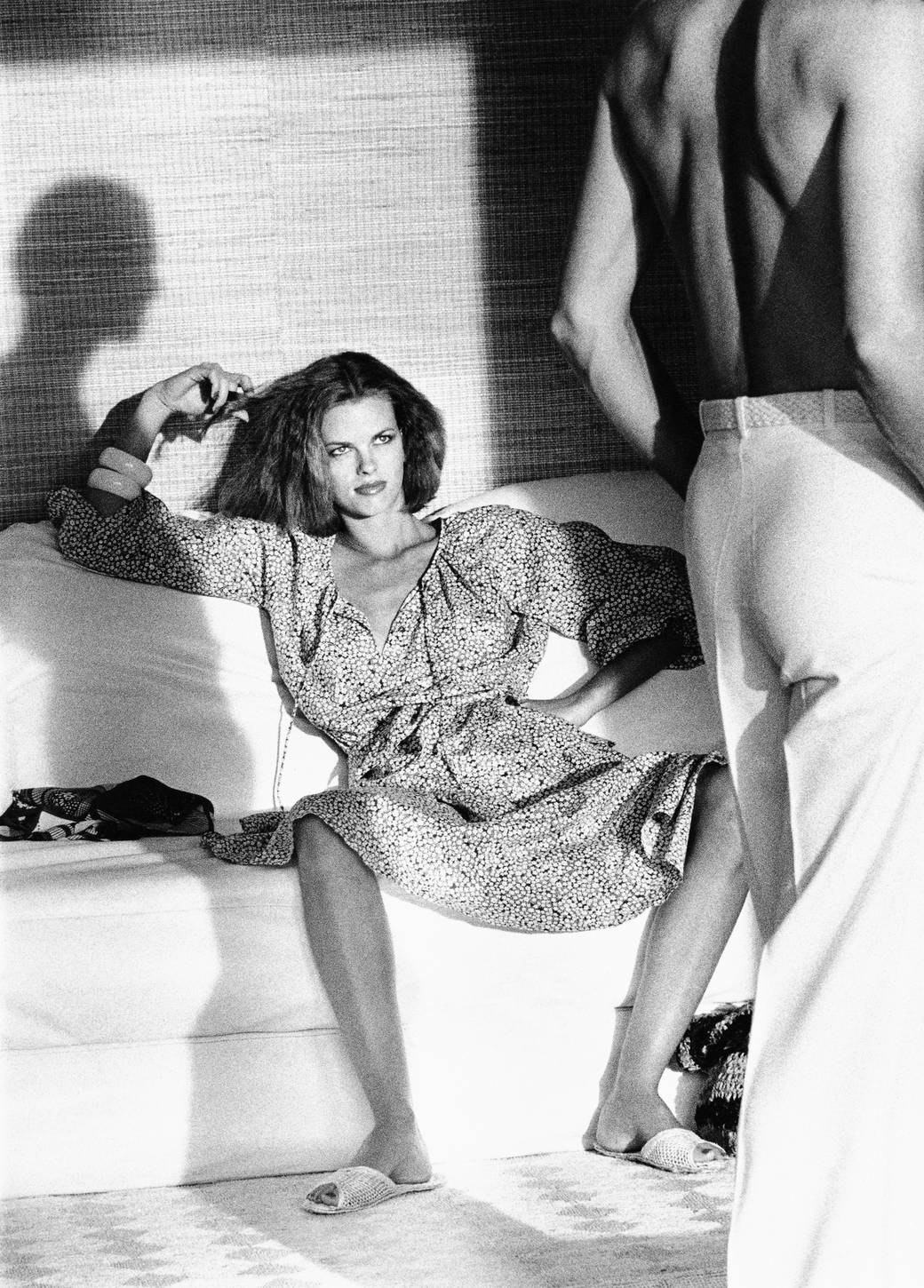

Enter Berlin-born, internationally famous photographer Helmut Newton. Newton was a cultural provocateur; some people called him the “king of kink.” He is nearly single-handedly responsible for bringing alternative sexuality into the mainstream of fashion. Sexually dominant women, roleplay, sexual role reversal, same-sex relationships, and even S&M permeated fashion through Newton’s unique vision.

The very publication of Helmut Newton’s fashion photographs of the 1970s exemplifies that mainstream acceptance, both in America and in Europe, but women’s liberationists decried his imagery and its influence. They said it further objectified and disempowered women. Despite those criticisms, there was tremendous power in this imagery, and that power was unquestionably handed to the women.

American Vogue, under editor Mirabella, notoriously published a fashion editorial in 1975 called “The Story of O.” It was a modern evocation of the famous erotic novel. The image Woman Examining Man, Saint-Tropez, 1975, was part of that editorial and became infamous. The all-American model Lisa Taylor takes on the pose of a man, her legs spread as a symbol of power, as she eyes and objectifies a shirtless, and faceless, male model. Male objectification, by a woman!

© The Helmut Newton Estate (Image courtesy of Maconochie Photography)

Later in the decade, with Woman into Man, Paris 1979, originally published in Vogue Paris, Newton took the male figure out of the picture altogether. In the French Vogue photograph, Newton alluded to a world where men were not needed for women’s pleasure at all—we had entered the land of the Amazons. Here, women could join together in same-sex relationships with impunity, and not just impunity, but with high style. This was a fetishizing of male gender display, and it is worth noting that perhaps from Newton’s masculine, and presumably cisgender, point of view, he was indulging in a mimicry of traditional male-female relationships. Nonetheless, Newton intentionally and ironically blurred the lines of gender display in a provocative way, and it was brilliantly decadent.

(Image courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Newton’s decadence was not for everyone, but acceptance of such a mindset into the pages of American Vogue, and the more exotic French Vogue, was an unmistakable marker of the sensibilities of the time.

Male power wasn’t gone from the scene by any means, at least not for long.

1980–1989

Building on the emerging mindset of the 1970s in regard to traditional male and female gender display and roleplay, the 1980s saw something new: the full-throated commercial objectification of the male form.

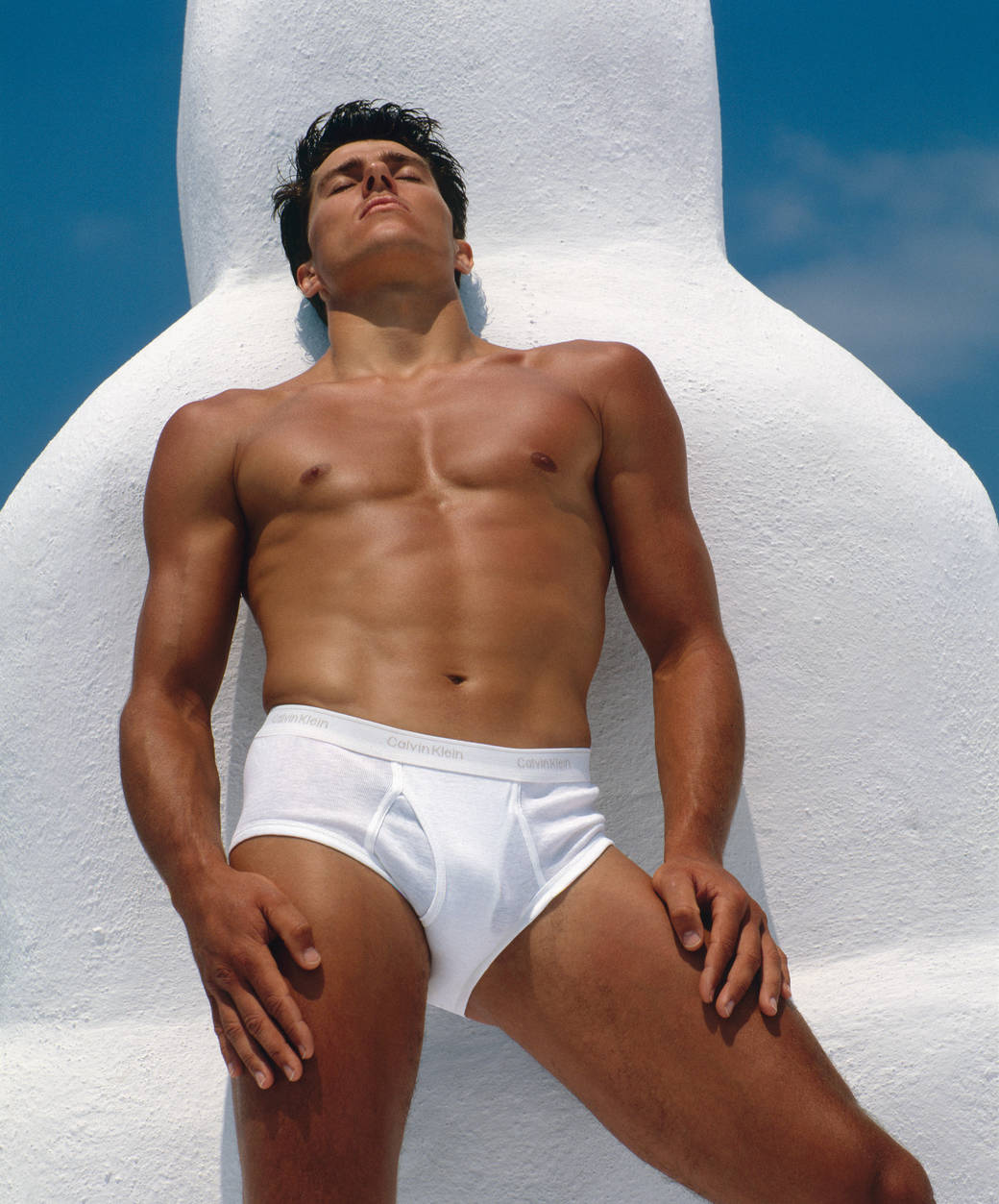

With the photograph Tom Hintnaus for Calvin Klein, Santorini, Greece, made by the American photographer Bruce Weber in 1982, the influence of homoerotic imagery in advertising was born. The photograph was initially presented as a four-story poster billboard in no less than Times Square, and caused a major sensation.

© Bruce Weber

As the decade progressed, it was time for the scales to shift. If we had objectified the female form and sexuality in fashion photography for nearly 80 years, well, now it was the men’s turn. Which begs the question: Is sexual objectification acceptable? No matter if that objectification is of a male, a female, or a non-binary display, the answer to the question may depend on what one’s idea of acceptable is. But no doubt it was entertaining, and let’s never forget that the wheel of fashion often turns on novelty and titillation.

The late 1980s saw several other major changes in the literal landscape of fashion. One was a move of venue. Los Angeles, believe it or not, began to take an important place in the hierarchy of fashion capitals. The fashion media focus began to turn away from models and on to celebrities (in many ways thanks to Andy Warhol and his fetishization of fame). Celebrity was on the rise. It wasn’t enough to be a beautiful but unrecognizable model anymore. By the end of the decade, in order to compete with the culture of celebrity, the models had to become celebrities themselves. Thus, the '80s supermodel was born.

A particular group of models, the so-called ‘supers,’ seen here in an iconic image by Los Angeles-born photographer Herb Ritts from 1989 entitled Stephanie, Cindy, Christy, Tatjana, Naomi, Hollywood, marks that moment indelibly. And as the ethos of Hollywood and celebrity became primary in the worlds of fashion, beauty and luxury, Los Angeles itself began a slow rise.

© Herb Ritts Foundation (Image courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

We are literally enjoying the results of that rise today. Los Angeles may not be one of the primary fashion capitals, but it is unquestionably the capital of Western lifestyle culture and celebrity. And now, in yet another another shift, the city is taking its place in the highest levels of the world of contemporary art.

Related

podcast

Episode 15: Matthew Rolston on Glamour, Death Anxiety and the Unity of Opposites

September 18, 2018

video

CHANGE/MAKERS: Matthew Rolston

December 14, 2016

profile