profile / exhibitions / alumni / art

May 05, 2017

Writer: Solvej Schou

Images: Courtesy of Mike Saijo, and

Japanese American National Museum

DREAM DEFERRED: FINE ART ALUM MIKE SAIJO'S WORK FEATURED IN EXHIBITION ON INTERNMENT OF JAPANESE AMERICANS DURING WWII

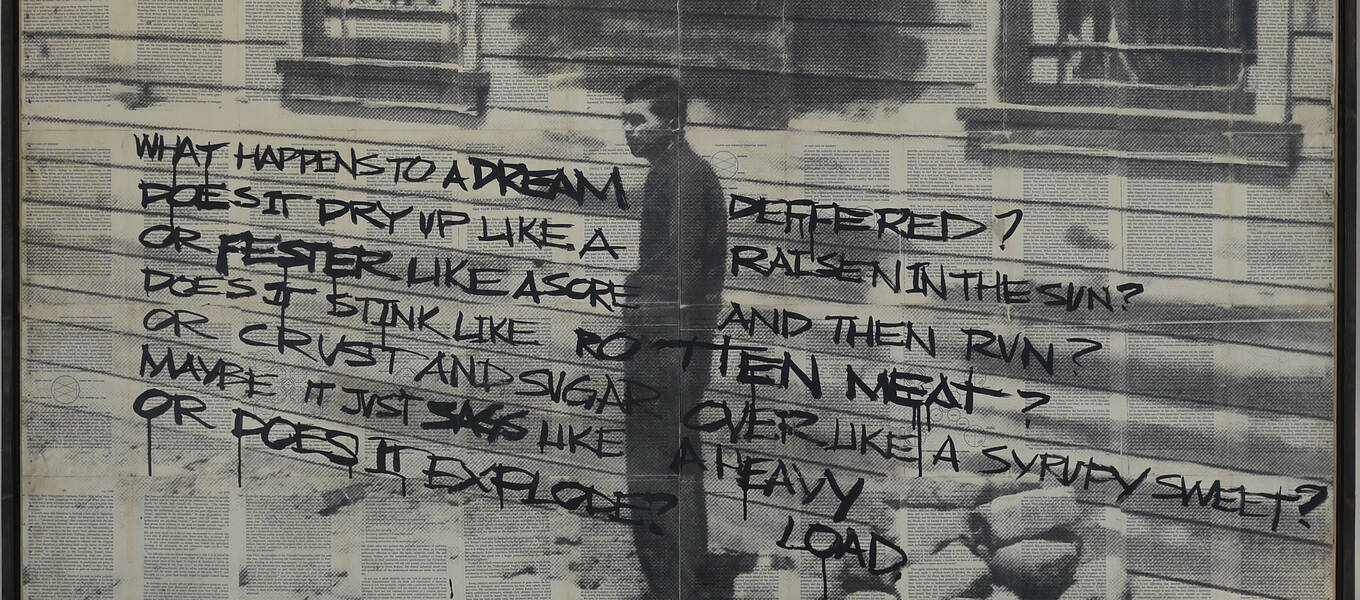

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

Like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

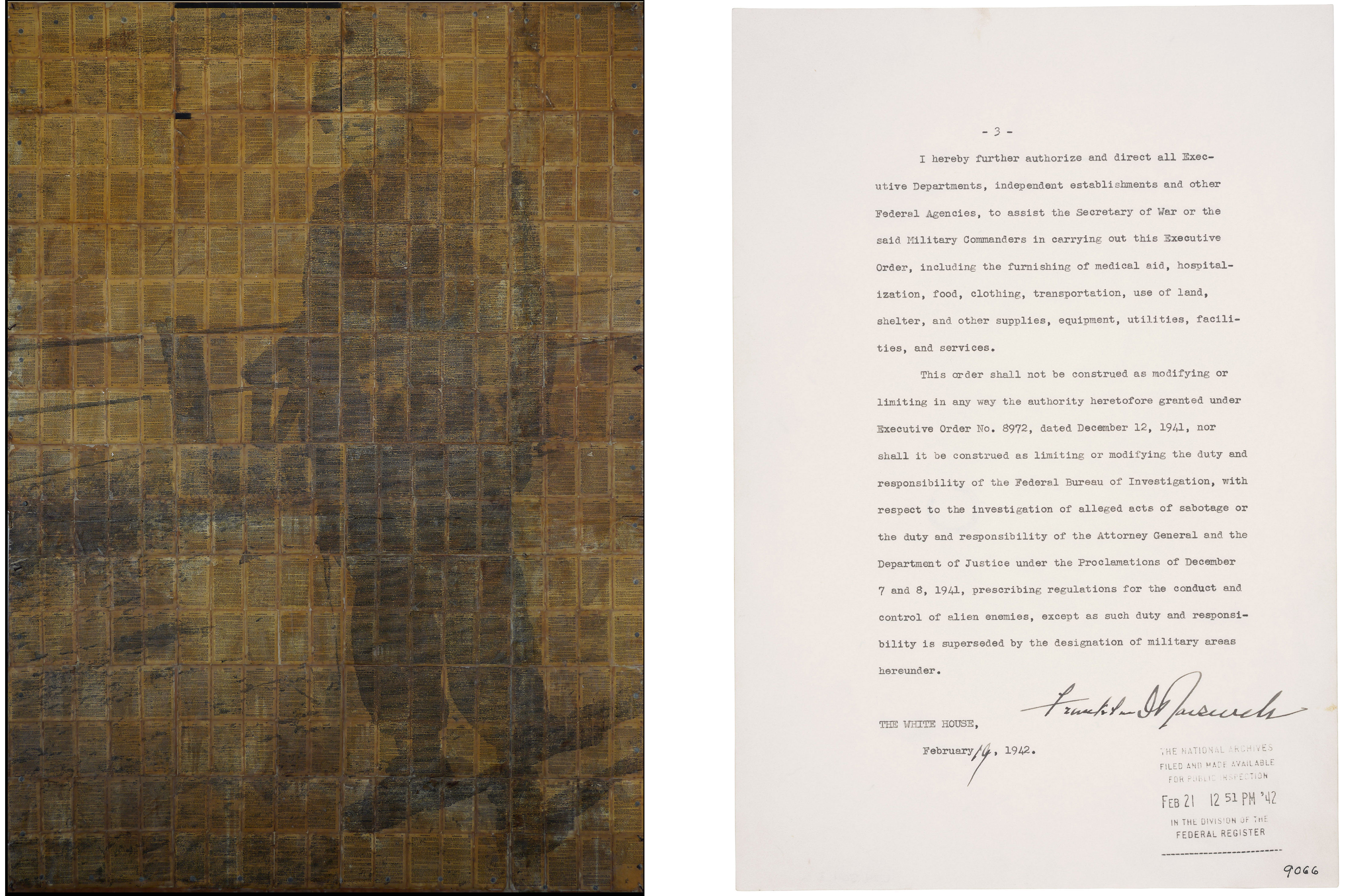

On a recent day, Fine Art alum Mike Saijo stands and reads out-loud those words—from African-American writer Langston Hughes’ 1951 poem “Harlem”—scrawled across his 2011 artwork Dream Deferred, hung in a dimly lit room at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM) in downtown Los Angeles.

Beneath the words is an enlarged photo, taken by photojournalist Dorothea Lange, of a Japanese-American man in front of a barrack in the California internment camp Manzanar during World War II. The photo is Xerox printed across book-sized pages of text—lined up side-by-side and top-to-bottom, and mounted on a wood panel—from historian William Irwin Thompson’s 1971 book At the Edge of History. The man looks off into the distance. Splotches of black paint drip down from Hughes’ emotional words.

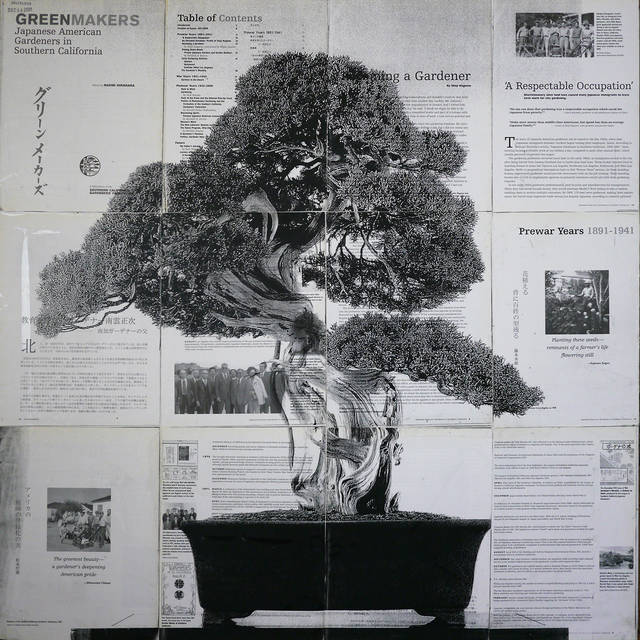

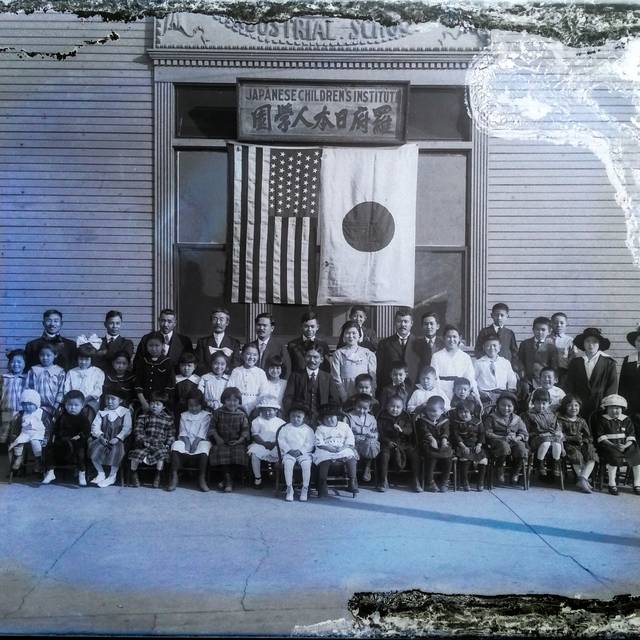

The piece is one of three works by Southern California born-and-based Saijo—himself the son of Japanese immigrants—in the exhibition Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066 at JANM through August 13, 2017. Signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, after Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, Executive Order 9066 led to the forced removal and imprisonment from 1942 to 1945 of 120,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Along with original documents and documentary video, the exhibition explores the impact of language, profound pain of that time and experiences of Issei (first generation Japanese-born immigrants) and Nisei (second generation Japanese Americans born in the U.S.).

“Langston Hughes’ poem really expresses what Japanese Americans might be feeling then,” says Saijo, wearing a crisp white button-down shirt and a yarn and crystal necklace from Peru. He describes his more than two decades-long career as an artist as “a contemporary approach to historical subjects, with reconstruction of memory.”

“Japanese Americans dressed Western. They were assimilated. They wanted to fit in. They were trying to do their best,” he says. “Having made art quite a bit about Japanese-American history, I feel that the concept of memory reconstruction starts to make sense, especially with our awareness of memory, of the past, being jeopardized. It feels important to bring history to the present, and for the work to shape our view of the current political situation, and reflect on the past.”

It feels important to bring history to the present, for the work to shape our view of the current political situation, and reflect on the past.

Mike Saijo

Saijo had originally created Dream Deferred for a 2011 L.A. exhibit of the same name. It was about the connections between different communities in the face of World War II, from Japanese Americans being sent to concentration camps to L.A. Mexican American youth in the Zoot Suit Riots to the experience of Jews.

“For me, the interaction between different ethnic groups is meaningful,” says Saijo. “Hughes’ poem is also a bridge between the black and Japanese-American communities, with the human condition being the underlying theme. I lived in an L.A. hip-hop recording studio when I created the piece. Rappers saw me—a Japanese guy who knew what’s up—and we were able to share our experiences.”

Raised in the San Gabriel Valley, with a father who came from eight generations of rice farmers in Japan, and a mother who taught Japanese calligraphy before going into banking and real estate, Saijo discovered his love of art and knowledge early on. He started doing expressive calligraphy line drawings when he was 6, and spent hours at the library with his younger brother.

“My mom wanted me to go into finance or engineering, something more stable,” says Saijo. “Art for me was an act of resistance.”

Saijo did graffiti, listened to hip-hop, got into fights at school, did judo for eight years and “dressed like a gangster.” He also took ArtCenter for Teens (then Saturday High) art classes, and even saw Keith Haring create his 1989 ArtCenter mural at the Hillside Campus. He wanted to talk to Haring, but was too nervous, he says. He graduated from high school in 1992, the year of the L.A. riots.

When he was just 17, for a Pasadena City College (PCC) art class taught by Japanese-American artist Ben Sakoguchi, who spent his early childhood in an internment camp, Saijo created 1993’s Soldier, another piece in JANM’s Executive Order 9066 exhibit. He used the same technique that set the stage for his later work, such as Dream Deferred.

“Right out of high school, I knew I wanted to become an artist, and I really wanted to make a piece that represents this history, and reclaim it,” says Saijo.

Soldier features a photo of late Hawaii U.S. Senator Daniel Inouye as a smiling young platoon sergeant in the segregated all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team. (Inouye went into the U.S. Army when it dropped its enlistment ban on Japanese Americans in 1943, and took volunteers from internment camps).

Saijo printed the photo across pages of a New Testament bible issued and published by the U.S. Army in the early ‘40s and given to a friend’s Japanese-American uncle who had served in the Korean War. Over the years, Saijo put wax and resin over the piece, preserving it.

“I wanted to develop a different visual language, and not use conventional art mediums. Using the pages of a book tells a story, juxtaposed to an image,” says Saijo. “I was seeking an identity, of who I am and where we are now. History established that sense of grounded reality.”

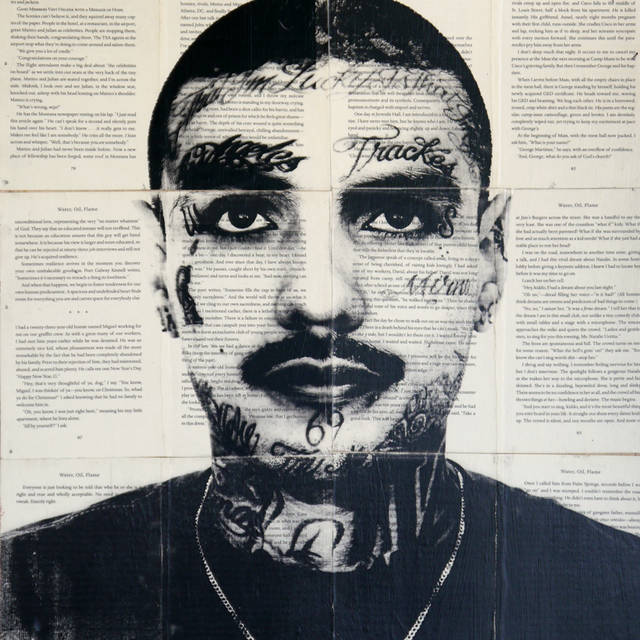

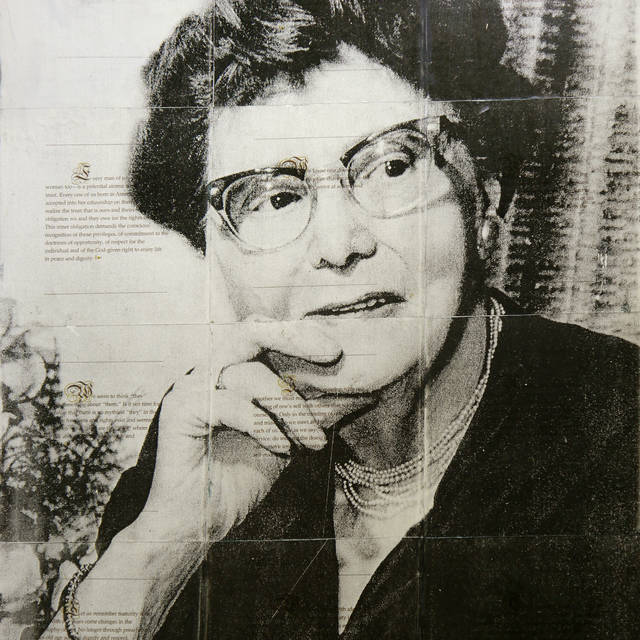

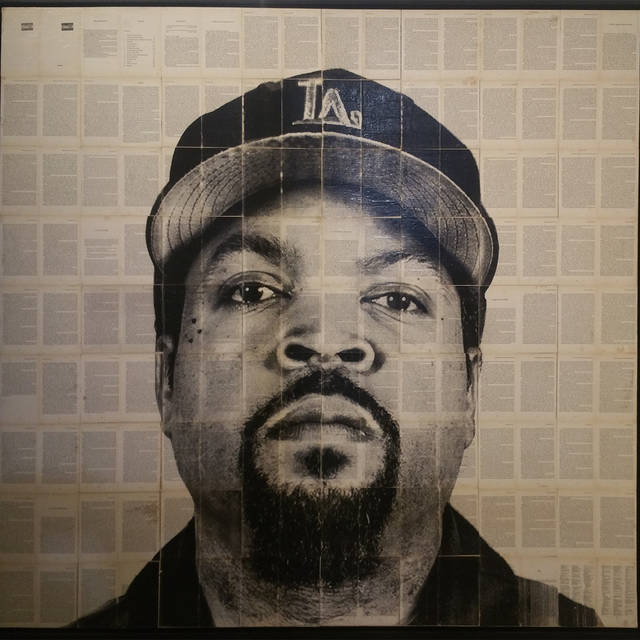

OTHER WORK BY MIKE SAIJO (CLICK IMAGE TO VIEW GALLERY):

What sold Saijo on ArtCenter, after taking classes at PCC, was the Hillside Campus’s modernist steel-and-glass architecture. “The building was just too beautiful,” he says.

His favorite classes included an academic course called Myths and Mysticism, where Saijo learned about meditation, shamanism and indigenous cultures. Saijo was also inspired at ArtCenter by late legendary artist Mike Kelley, who taught in the Graduate Art Department. Saijo sat in on his classes, as well as classes taught by post-conceptual artist Stephen Prina.

After living and working in New York City, after ArtCenter, Saijo returned to L.A., doing art pieces through the years with a focus on cultural exploration and community capacity building. Other work within L.A.’s downtown Little Tokyo neighborhood, where JANM is located, include an upcoming Spiritual Legacy Project series sponsored by the Little Tokyo Historical Society. That series will revolve around pre-World War II images of L.A.’s first generation Japan-born immigrant community discovered in a collection of glass plate negatives—images that hadn't been seen in 100 years.

“The Issei pioneer story is a really important part of our past and our relationship to our ancestors that we need to honor and remember,” says Saijo. “We’re connected to something greater than ourselves.”