Diana Thater’s Sympathetic Imagination

She’s snorkeled with wild dolphins, regularly watches the Nat Geo channel and lives with four rescue cats. So it seems only natural that Graduate Art Chair Diana Thater (MFA 90) would use her empathy for animals as the foundation for a remarkable series of video and film installations dissecting the knotty dynamic between humankind and wildlife.

© Diana Thater, photo by Volodymyr Palylyk

Sipping an espresso in the cozy Highland Park studio and home she shares with artist/musician T. Kelley Mason, Thater, dressed in a hoodie, black pants and sandals, says, “When I go on shoots, I find my relationship to the animals is very different from that of the crew. They’re not alien to me.”

As stray Spiffy insinuates himself alongside her on the sofa, Thater elaborates. “I’ve had very close contact with gorillas, wild dolphins, chimpanzees. I’ve had monkeys climbing all over me, I’ve petted a tiger. You have to be really open in order to work with animals in that way,” she laughs. “I hope I am.”

For more than two decades, Thater has remained profoundly open to unexpected discoveries, trekking to remote locations to capture footage for her nature-themed media art pieces. She says, “I’m always looking for interesting subjects because I feel, in a way, it’s my job to document the state of the natural world in art before it all disappears. That’s really a mission for me.”

Thater’s ongoing investigations have earned rave reviews in New York, London and Europe but rarely in Los Angeles. “I’ve gotten nothing but trouble from the local critics and hardly ever show in L.A.,” she says.

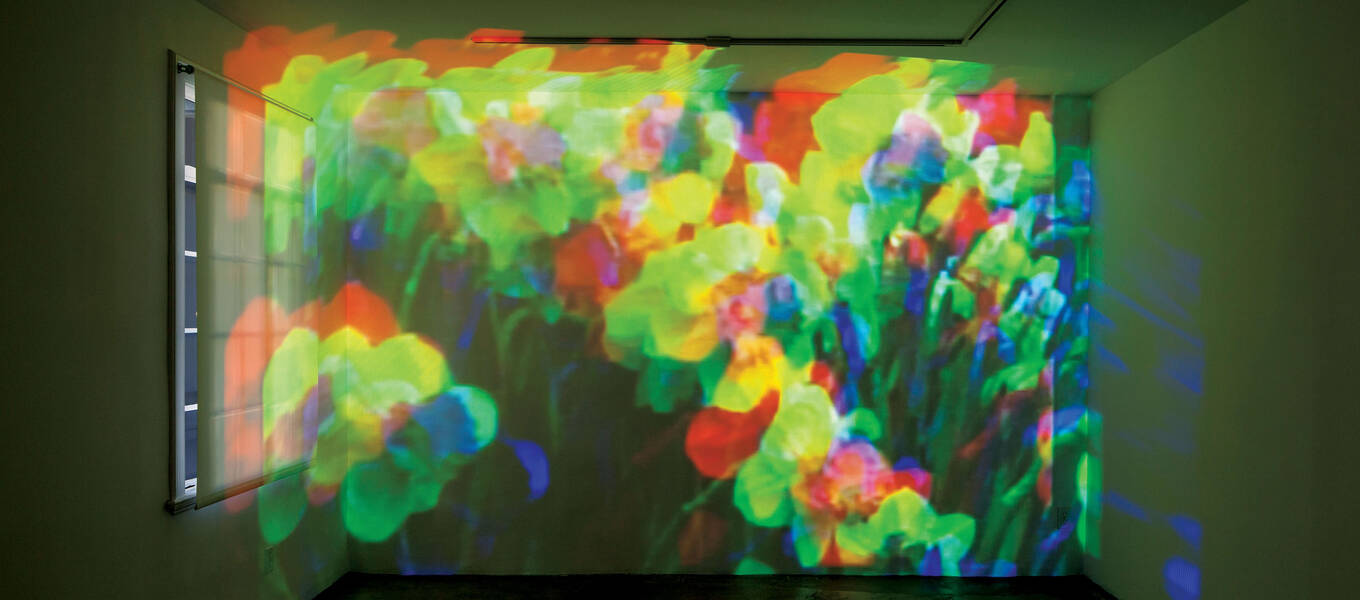

Video projector, player, and Lee filters; dimensions variable.

Installation view at 1301PE, Los Angeles, 2012

Photo © Fredrik Nilsen, courtesy 1301PE, Los Angeles

That changes this fall when the Los Angeles County Museum of Art presents Diana Thater: The Sympathetic Imagination. Opening November 22 and running through February 21, 2016, the 20,000-square-foot retrospective takes up an entire floor of LACMA’s Art of the Americas building and the top west side of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum. It represents the largest monographic exhibition dedicated to a female artist in the museum’s history. Works range from 1992’s Oo Fifi, Five Days in Claude Monet’s Garden, which separates video images into red, blue and green components, to her 2015 Life is a Time-Based Medium, a three-channel video installation inspired by the 18th-century Galtaji Temple in India currently occupied by wild monkeys.

LACMA Director Michael Govan has championed Thater’s work since 2001, when he presented her bee-themed installation knots + surfaces at Dia: Chelsea in New York. After LACMA acquired several Thater pieces, the museum’s Christine Y. Kim, associate curator of contemporary art, began organizing The Sympathetic Imagination. Kim, who also curated light and space pioneer James Turrell’s 2013–2014 LACMA retrospective, believes both artists design environments that transform the way viewers perceive the world.

“With James Turrell, when you go into the Perceptual Cell—the ‘God cell’—you feel the hair stand up on your skin, your pupils dilate, you go into an alpha state, your eyes adjust and you start seeing something in what had appeared to be a completely black room,” says Kim. “In a totally different way, Diana’s arranged these shifts and inversions to occur in real time, with scale, with palette, with movement, with animal behavior. Those strategies turn notions of beauty on their head. It’s not like a Sunday painter’s landscape beauty or the beauty of nature or the beauty of abstraction. It’s about all of those things. Diana’s work is very invested in the viewer seeing how he or she sees.”

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Alex Delfanne

Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth

Photo: Alex Delfanne

From Spectator to Artist

Thater’s path to midcareer retrospection took a pivotal turn 27 years ago when she arrived at ArtCenter to begin MFA graduate studies. Thater had been working as an architect’s assistant in New York after earning an art history degree at NYU. “In the East Village and SoHo, I’d go to shows by my heroes, all the great female artists working in New York at that time like Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, Cindy Sherman,” Thater recalls. “I longed to be an artist, but I was a spectator.”

When Thater moved west, she says, “It was a revelation. All of a sudden, I was among all these amazing artists. And they were friends with Barbara Kruger and eventually I became friends with Barbara because I became friends with my teachers after I graduated. So when I got out here, I became an artist. I was accepted into this group who became the most important people in my life: my favorite artists, my teachers.” Those teachers included video art instructor Patti Podesta, who remembers Thater as a quick study.

“Diana’s insanely smart,” says Podesta, now a production designer teaching part-time at ArtCenter. “From the get-go, she understood the relationship between aesthetics and technology by making these conceptually tough works about nature.”

The late Mike Kelley also figured as a key influence in Thater’s creative evolution as mentor, role model and next-door neighbor. (She and Mason bought their vintage 1904 building 10 years ago at Kelley’s urging.) “Mike’s work was very deep, but it didn’t really influence me as much as his way of living and being an artist,” explains Thater.

Mason worked as Kelley’s studio manager; Thater learned by watching. “T. Kelley traveled with Mike to install his exhibitions so I’d tag along. Mike had a very clear idea about how his work should be presented and by following him around, I learned really vital things. How do you do a big exhibition? How do you work with a museum? How do you choreograph your work? You can’t be easygoing about it. You don’t walk in thinking, We’ll do it when I get there. You figure it all out beforehand so no one can change the meaning of the work by altering the fit contextually.”

I want to deconstruct the animal as the object of our observation, object of our affection, object onto which we project all kinds of guilt and human feelings and human emotions. And I want to reconstruct them, or allow them to reconstruct themselves, as complex subjects.

Deconstructing Dolphins

Emboldened by Kelley’s example, Thater has produced a steady stream of architecturally sophisticated installations that undercut the artifice of anthropomorphic storytelling.

“I want to deconstruct the animal as the object of our observation, object of our affection, object onto which we project all kinds of guilt and human feelings and human emotions,” she says. “And I want to reconstruct them, or allow them to reconstruct themselves, as complex subjects.”

But like her favorite songwriter Bob Dylan, whom she’s seen in concert more than 50 times, Thater steers clear of overt messages. “I am interested in both art and activism but I am not interested in intermingling them because then it becomes too messy,” she says.

Art is like a knife: It needs to be pointed and incisive. I think activism has to be the same way. They shouldn’t be muddled up together.

Thater considers her work on behalf of the Dolphin Project as a clear-cut exercise in proselytizing. After filming a pod of wild dolphins in the Caribbean, she made Welcome to Taiji in 2004. Designed to trigger outrage, the 25-minute documentary garnered 200,000 views on YouTube and inspired director Louie Psihoyos to make 2010 Oscar winner The Cove about the same subject.

“As an activist,” she says, “The whole point is to spur people to do something. I worked on Taiji very specifically to expose the Japanese dolphin slaughter.” By contrast, she configured dolphin imagery in her installation Delphine to serve a different purpose. “I’m bringing this rarified natural world into the art world in order that people may contemplate it.”

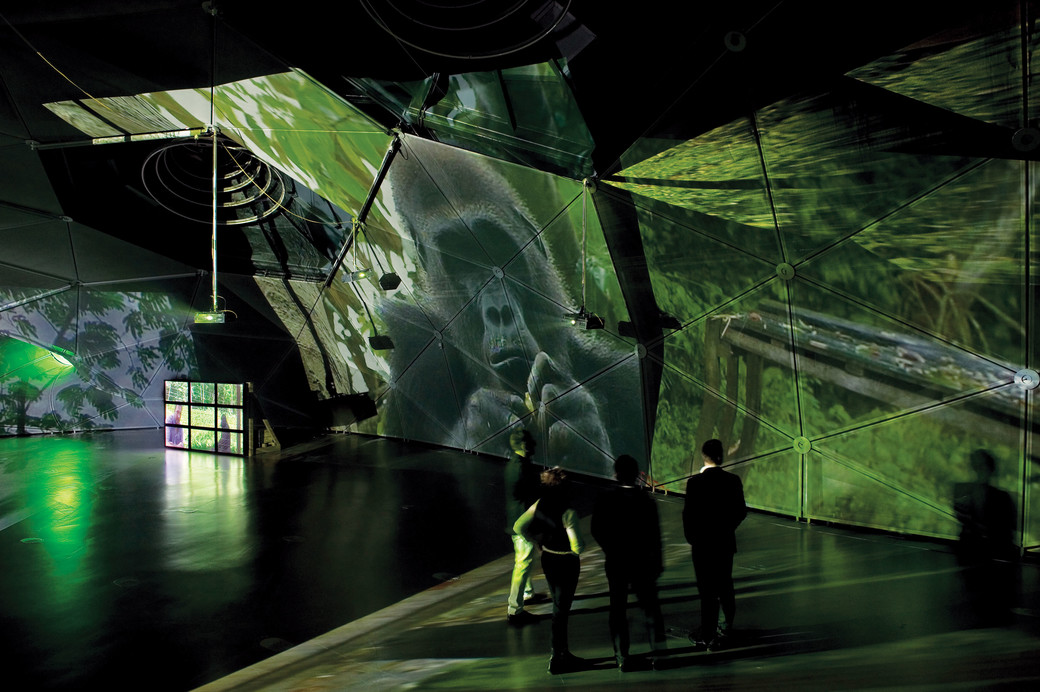

Anyone who knows me knows I’m not insulting anyone when I compare them to a gorilla, because there’s nobody I like better than a gorilla.

Kunsthaus Graz, Austria (2009) Photo: Universalmuseum Joanneum/N. Lackner

The Artist’s Practice as Mentorship

Thater maintains a vital presence at ArtCenter when she’s not filming primates in Cameroon (gorillagorillagorilla), tracking falcons in the Santa Monica Mountains (Here is a text about the world), documenting elephants in South Africa (RARE), studying dung beetles in Arizona (Science, Fiction), capturing images of migrant butterflies in Mexico (Untitled videowall [Butterflies]) or bearing witness to the wild horses that walk through abandoned Ukranian villages (Chernobyl).

“People say to me, ‘Oh you have so many adventures!’ but I think I’m quite boring really,” Thater says dryly.

An ArtCenter teacher since 1994 and Grad Art faculty chair since April 2014, Thater has influenced scores of young artists. They include Jennifer West (MFA 04), whose experiments in celluloid-based artworks include her Skate the Sky Film installation at London’s Tate Modern, in which skate boarders rolled over strips of 35 mm celluloid. “Diana taught me about this lens that I could look at art or film or ideas or philosophy through,” says West. “Diana taught me to think about how subject and form intersect and how you can influence the meaning of any given work through that kind of collision.

I didn’t have that way of thinking before I studied with Diana and it became a very influential component of my work.”

Kunsthaus Graz, Austria (2009) Photo: Universalmuseum Joanneum/N. Lackner

Grad Art Associate Chair Jason E. Smith notes, “Diana has a very strong sense of what it means to be an artist today and this colors her approach to the tasks of directing the program, and how she relates to students.” Thater adds, “Jason and I believe the Graduate Art Department is a community. It’s not about crushing people and having them build themselves back up. I’ve seen that in action and don’t like it. I prefer the supportive approach.”

Thater embraces the notion that the practice of art, in itself, can serve as a powerful form of mentorship. “It’s important to recognize we are role models for our students because I know they’re looking at us the way I looked at Mike Kelley and Patti Podesta,” she says.

“I’d just imitate them until I’d taken it all in, and I suspect that’s what students do with their teachers.”

For studio visits and crit sessions, Thater coaxes fresh thinking from her charges in much the same way that she connects with cryptic creatures of the wild. “I think I must approach young artists like I approach gorillas,” Thater says, holding out her hands, palms up. “‘Show me who you are and let’s have some kind of back and forth about it.’ You don’t want to tell students what to think about. You want to help them figure out how to think.”

Thater pauses, then laughs. “Anyone who knows me knows I’m not insulting anyone when I compare them to a gorilla, because there’s nobody I like better than a gorilla.”

Related

feature

A World of Magic: ArtCenter for Teens Photo Class for Students with Special Needs

March 14, 2017

impact-90-300