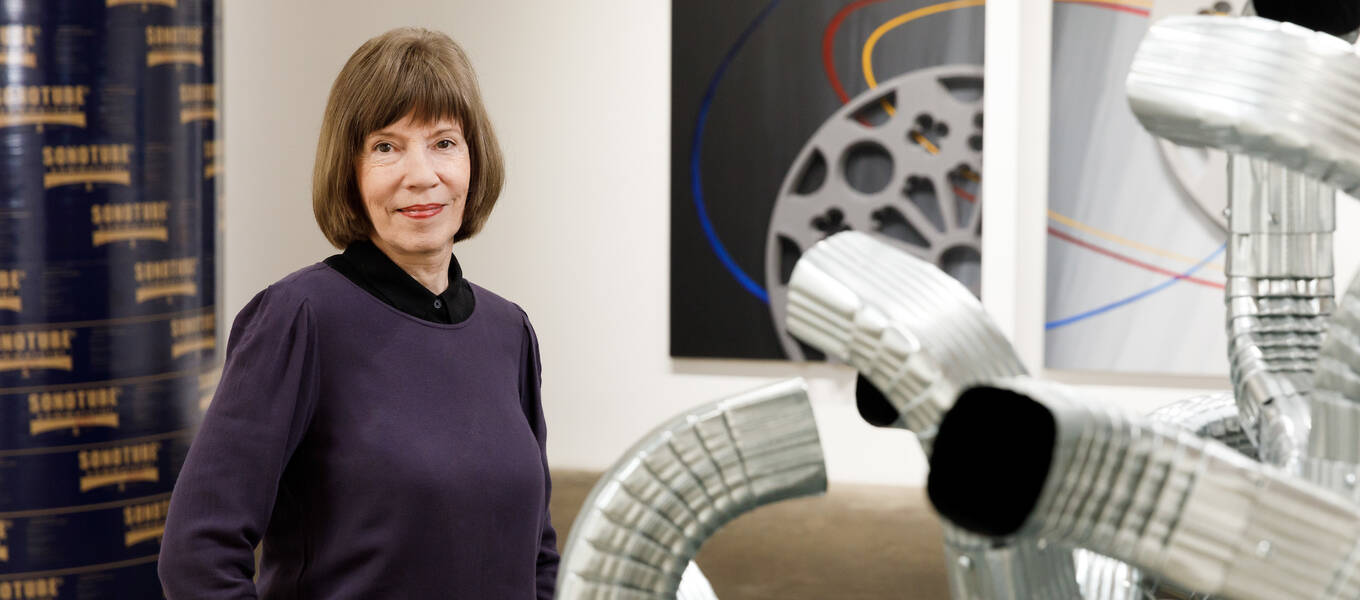

Concepts Are Not Enough: Alumna Lynn Aldrich Finds Beauty In The Physical Nature of Things

Lynn Aldrich (MFA 86 Art) doesn’t seem to be able to make up her mind. She wants objects—hard, cheap, common objects—and ideas as well. And the ideas can get big—philosophical, celestial, even: She wants her art to be vehicles for them, even if the materials she uses come from 99 cent stores and Office Depots.

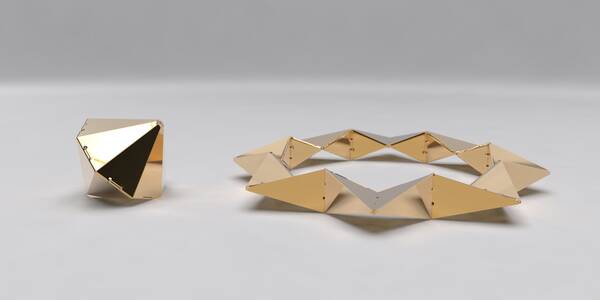

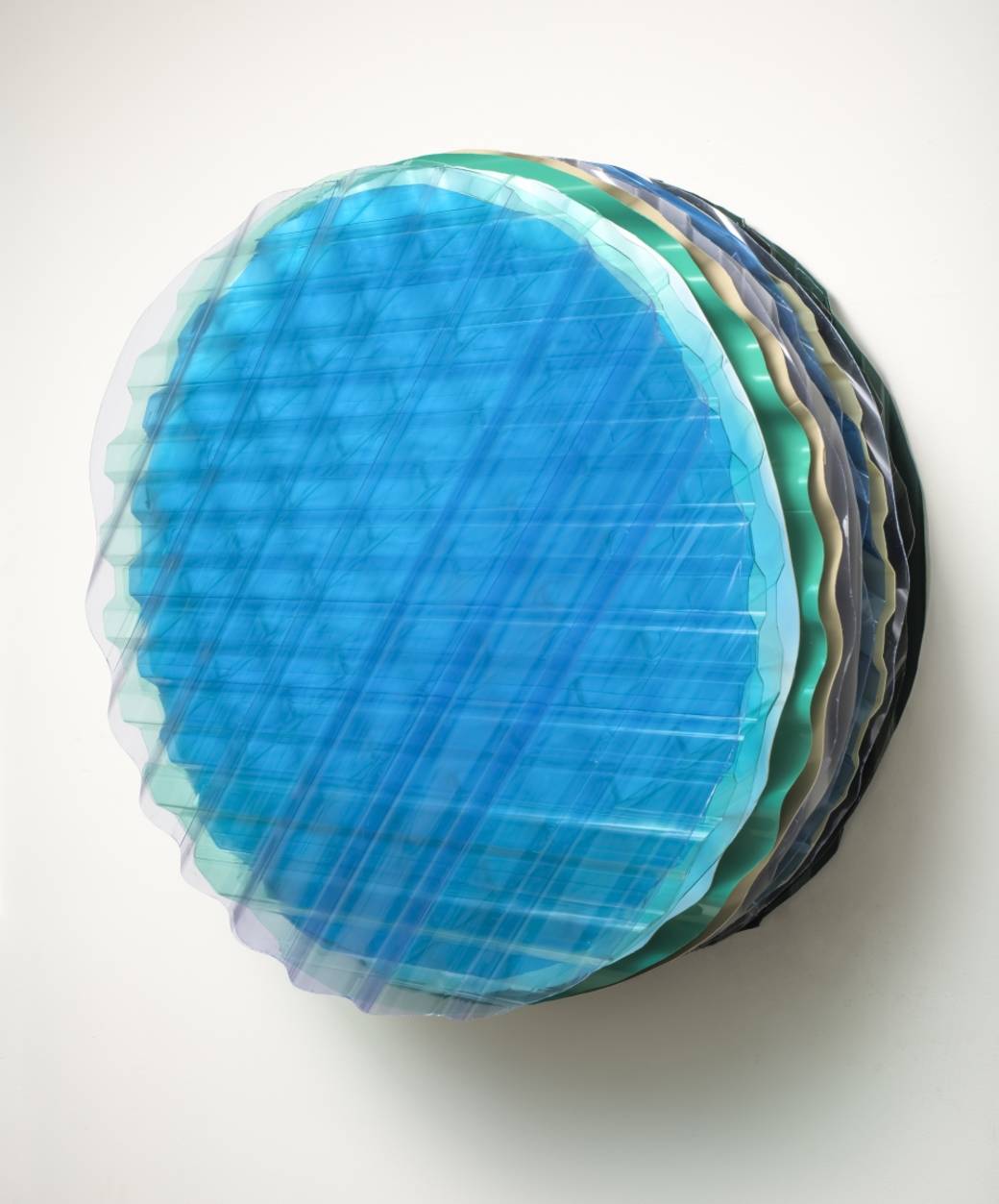

She loves Minimalism—especially the work of Donald Judd—and what she calls “the ethics of minimalism: That you should not be deceitful about your materials.” But she goes beyond Minimalist orthodoxy in her sense of how art works: No matter what the piece is, “We always bring our associations.” That’s why a stack of paper plates can turn into an ancient Greek column, or an array of rainspouts can become something lovely and mysterious that seems to belong in Renaissance Italy. Speaking to Aldrich, you realize she lives in the world, and on the astral plane at the same time.

It may be difficult for Aldrich to reconcile her dialectical imagination. But the winner in this struggle between object and idea, head and heart, Apollo and Dionysus, is the curious person who encounters Aldrich’s work, some of which is currently on display at DENK Gallery in downtown Los Angeles.

Howard Fox, the emeritus LACMA curator who has known Aldrich for decades, describes the show as almost “a mini retrospective” in which “something thoughtful and reflective is going on.”

Aldrich is not unaware of her divided soul. “I’m interested in materials, and as a realist I sought out materials that would retain the ordinariness of their being, disconnected from metaphor or meaning,” she said recently. “I have this desire for the romantic. I have two sides, the realist and the romantic—I can’t shake it.”

Some of her complex ambitions come from her formative years. Aldrich was born in East Texas and grew up a military brat who moved every few years. Her early interests were the sciences and literature; she studied English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She and her husband moved to the Glendale hills with their young sons in the early 1970s. About a decade later, she enrolled at ArtCenter—she recalls Graduate Art as “a small, intense program trying to grow”—and studied with Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe. There she began to find her direction.

“I was lucky enough to be at a school—ArtCenter—that was aware of beauty, of the physical nature of things.” She had been captivated by the Conceptual Art of John Baldessari. But concepts weren’t enough. “I wanted to make something beautiful, something to look at.” The program later helped launch her by introducing her to a network of galleries and other artists. “You have models, people who’ve done this before you.”

“My art is not about me psychologically or about my identity,” she says now, standing in her 1950 ranch house she describes as “Midcentury Modest” and which is adjacent to her actual home. “It’s about my outward gaze on the world. I think artists share that with scientists.”

You see some of this impulse in the work at DENK—some made from fake rocks, discarded ink cartridges, or the store-bought Sonotubes that become an almost monastic retreat from an over-stimulated world. You see it in her piece Rose Ghost, which hangs in her studio and echoes both the windows of an Italian cathedral and California’s 1960s Light and Space movement.

Her style also comes from Aldrich’s natural temperament, what Fox calls, “down-to- earth but with lots of ethereal dimensions.”

Aldrich taught at ArtCenter through the 1990s but has devoted herself entirely to her art for a dozen years now. That “Midcentury Modest” ranch house? She’s aiming to convert it into a gallery and art destination, like a miniature Marfa or Dia Beacon. “I have a connection to the banal ordinariness of suburban living.”

Aldrich did something unusual in her DENK show: She included several pieces from her early years, paintings built upon found objects that riff on artist heroes like Van Gogh and Robert Smithson. One nods to an iconic painting by Caspar David Friedrich, the 19th century German Romantic who worked during a period of intense transformation. Aldrich sees artists as living through something similar today. “Artists can either jump in and address the digital world,” she says, “or step back and say, ‘Look at this.’”

Chances are, she’ll do both.

Related

feature