feature / alumni / faculty / students / environmental-design / industrial-design / graphic-design / illustration / interaction-design / product-design / sponsored-projects

December 01, 2016

Writer: Mike Winder

Let’s Play

Toy design for a new generation

“The way I explain toy design to students is, don’t think about the toy as an object,” says Krystina Castella. For the past 24 years Castella has taught in both the Graduate Industrial Design (Grad ID) and the Product Design departments, and these days her most popular course is Toy Design. “Design an experience,” she continues, “and think of the toy as the tool to bring about that experience.”

This warm spring day finds her at toymaker Mattel’s headquarters in the city of El Segundo, about three miles southwest of LAX. ArtCenter students enrolled in a sponsored project are busy presenting their concepts for the future of vehicles—of the 1/64 die-cast variety—to an auditorium packed with the company’s designers and executives, many of them College alumni.

As lead faculty for this project, a transdisciplinary studio titled The Future of Play, Castella, along with instructors Adam Voorhees (BS 09 Environmental) and Ania Borysiecvicz (BFA 99 Graphic), guided a class of 16 students tasked with designing a 2025 toyline for Hot Wheels, Mattel’s most lucrative property. For their research, the students observed children and their play patterns, explored the latest toy trends, investigated near-future technology, prototyped concepts, and tested their ideas at Kidspace Children’s Museum in Pasadena.

And now the big day is finally here.

The students’ projects propose solutions to many of the challenges currently facing the toy industry, including how to get kids to play outside and how to redirect them away from screen-based entertainment. The ideas vary wildly in scope, from Autolympia, a physics-based themed destination where Hot Wheels owners experiment with their vehicles in a variety of tactile environments, to Hot Wheels Go, an all-in-one playset-in-a-backpack that encourages kids to challenge one another, virtually and in the real world, to build elaborate outdoor racetracks.

The audience is impressed. “Autolympia resonates with us because destination spaces are a thing now and could still very well be in 2025,” says alumna Jini Zopf (BFA 00 Illustration), senior manager of Hot Wheels packaging design at Mattel, who sat in on several classes throughout the term to watch the students’ process and provide feedback. She adds that the company also liked the project’s proposed use of technology, including a scenario in which kids bring in their cars and have them customized, through augmentations, into other forms. “Taking technology and applying it to something tangible is very much ‘next steps’ for Hot Wheels,” Zopf notes.

Bridging the analog and the digital

Back at Hillside Campus to give a Career Chats lecture, Zopf has advice for students regardless of what field they might enter: “Design thinking is very important for leadership, because it means you’re not stuck in one discipline,” she says. “You’re looking at this greater design universe and plugging into it in unique ways. Remember, the skillsets you learn here at ArtCenter can be applied in very diverse ways.”

Indeed, the strategic systems thinking that was so integral to alumnus Dan Winger’s (MS 09 Industrial) graduate education at the College has served him well as a senior concept designer for Lego. Winger works at the brickmaker’s Creative Play Lab (formerly the Future Lab) in Los Angeles, a unit that functions like an internal startup to drive innovation within the Denmark-based company.

A former student in Castella’s business courses, Winger has worked on a number of “One Reality” projects—experiences designed to bridge physical and digital play—as part of the Future Lab. Dan says Lego also sees technology as central to future success in the highly competitive toy industry. “Our name was the Future Lab,” laughs Winger. “So yeah, we definitely embraced technology.”

Case in point: Winger helped develop Lego Fusion, a 2014 “app plus bricks” set that allowed users to transfer physical brick creations—simple 2D facades of residential or commercial buildings—into a town-building game for iOS or Android. An intentionally small-scale launch, Fusion was designed to gather learnings. “It was an experimental area for us,” says Winger of the set. “Also, like all the concepts generated by our group, it focused on the loop back to the physical.”

Not that digital doesn’t have its advantages.

Still in early access, Lego Worlds is the company’s answer to Minecraft. A natural next step for Lego, the game aspires to become the ultimate creative sandbox for the next generation. In Worlds, players explore and customize infinitely variable worlds, as well as create and play within structures and environments of their own design. “It’s like a cleanly organized bin of virtual Lego bricks,” says Winger of Worlds, which his group developed and handed over to another team. “It offers unlimited access to everything, plus no more sorting to find that red 2x2 slope in the pile.”

Girls just wanna kick butt

For fans of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, finding one small Lego in a bin would be an easier task than finding an action figure based on Rey, the lead character from last year’s blockbuster film—who just happens to be female. The absence of toys based on female protagonists is unfortunately nothing new, and has in the past been dismissed with the observation “girls don’t play with action figures.” But in the era of Katniss Everdeen, parents are demanding change—and they’re getting it.

Back in El Segundo, Mattel recently launched a much-celebrated Game Developer Barbie who sports a laptop and a surprisingly utilitarian outfit. But more significantly, earlier this year the company launched its DC Super Hero Girls line, which revolves around characters like Supergirl, Batgirl and Wonder Woman. A major multimedia collaboration with DC Comics, Mattel and Warner Brothers, the line also includes apparel, costumes, middle grade novels and online animated episodes.

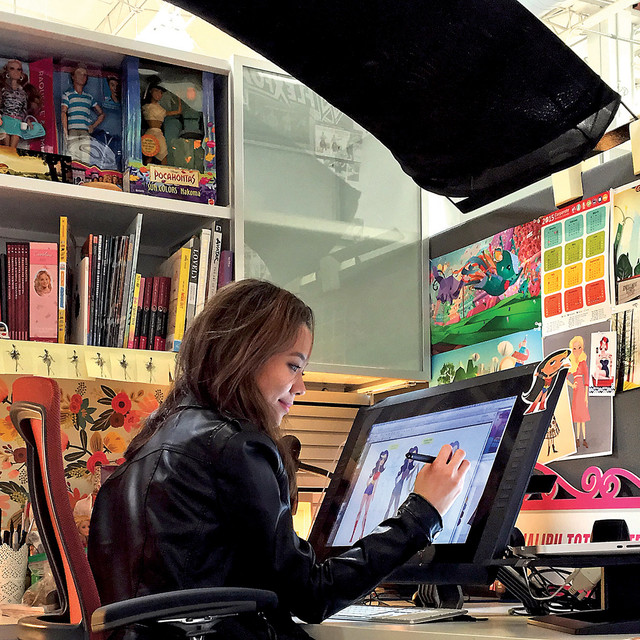

“DC has so many female characters with great stories,” says alumna Jenn Rahardjanoto (BFA 13 Illustration) of the toys that soft-launched at Target in March. A former art director at Mattel who was tasked with laying down the visual foundation for this new creative universe, Rahardjanoto took on the ambitious project just one year after graduating from ArtCenter. “But in the past they’ve been drawn in a pinup style that mostly appeals to men.”

After conducting research on what appeals to today’s girls and diving into DC character encyclopedias, Rahardjanoto emerged with 12-inch action dolls that differ from fashion dolls in significant ways. “They don’t wear high heels and short skirts, they wear flats or boots along with their iconic outfits,” says Rahardjanoto. “We’ve crafted their bodies to be toned and muscular. They stand on their own without a doll stand.”

And what do these girls stand for? “They stand for power, they stand for justice, and they save the day,” she says. “In our focus-testing groups, we saw 6-year-old girls saying, ‘Wonder Woman is going to save Barbie from the Dream House!’ Which is so great. They’re pretending to save their friends. That’s what it’s all about.”

Rahardjanoto hopes this groundbreaking line will usher in a new era of toys for girls. “Everybody who worked on this project really believed that this is the time when girls can feel like they’re super powerful,” she says. “We’ve all been so excited for this line to come out and to empower girls for generations to come.”

Is it working? Diane Nelson, president of DC Entertainment, recently told Forbes that the company thinks DC Super Hero Girls, which now has 70 product categories in over 35 markets after its wider rollout in July, could turn into a $1 billion brand.

Today, Rahardjanoto works as a creative director for GoldieBlox, a toy company dedicated to “leveling the playing field” with its construction sets designed for girls, with the ultimate goal of getting more girls interested in the field of engineering—a perfect fit for the designer. “I’m back to empowering future generations through new toys,” she says.

Let’s get physical

Whether it’s one element of a $1 billion brand or a stand-alone product, the ultimate purpose of a toy, as Castella points out, is to bring about a desired experience.

Creating a play experience is the goal of Play Studio, an Interaction Design course co-taught by department chair Maggie Hendrie and instructor and alumnus Todd Masilko (BS 96 Product). “When designing this course, we wanted students to focus on something that fell out of the bounds of screen-based app navigation,” says Masilko, a user experience designer whose career has included stints at Disney Mobile and Walt Disney Imagineering. “What the students ended up creating in class were experiences that were open-ended and not too prescriptive.”

Masilko points to two recent classroom projects by Shirley Rodriguez (BS 16 Product) and Interaction Design student Hari Ramachandran that embraced technology but didn’t fall into the trappings of “tech for tech’s sake.”

Created for children with juvenile arthritis, Rodriguez’ Monstas is an interactive toy that encourages kids to do their joint strengthening physical therapy. Winner of an IDEA Gold Award, a Core77 Design Award Noteable and a Spark: Concept Finalist, Monstas are three brightly colored characters, each of which focuses on different joints in the hand. They are squeezable, allowing them to be more easily gripped by children with painful joints, and made of conductive silicone, enabling them to act as an input device on a tablet. “I’ve always been interested in pediatrics, but I was shocked when I found out kids can have arthritis,” says Rodriguez, whose father is a physical therapist who works with the elderly.

Initially created in Product Design instructor Fridolin Beisert’s (MS 08 Industrial) Product Design 4 for the course’s theme “The Future of Medicine,” Rodriguez took Monstas to Masilko’s classroom with the goal of transforming the book-based activities into digital interactive experiences—exercises which, in either form, aligned with those prescribed to kids in a physical therapy clinic. Says Rodriguez, “The challenge then became transforming ‘Let’s tie our shoes’ into a fun interactive game like ‘Let’s make a pizza from scratch.’”

Designed for infants and toddlers, Ramachandran’s Bloom line takes classic playthings and gives them a 21st-century twist. In Masilko’s class, the Interaction student reimagined one of the world’s oldest toys—building blocks—by outfitting them with lights, sounds and vibration. When coupled with a video chat app, the blocks allow families to play together via physical interactions whether they’re sitting next to each other or across the globe.

“We’re living in a world that’s connected digitally, but increasingly disconnected physically,” says Ramachandran, whose Bloom allows users to simply slide their fingers across a screen to bring a block to life. The innovative toy was inspired in part by his childhood, when his father would have to travel weekly for his work. In class, Ramachandran discovered that his experience was one that many people found relatable. He adds, “In my research, one parent told me, ‘If I’m in a cab in New York after a long day of work and I can just pick up my phone and make my kid laugh? That would really make my day.’”

What tickles Masilko is that Bloom essentially replicates a style of play that’s existed since the Ice Age, but enables it to happen from a distance. “The imagination and fun that happens comes from the two people using the toy,” says Masilko, who posits commercial toys are sometimes so plugged into a company’s branding and story portfolio that it constrains play. “Sure, you can create all this media and software that updates, but that might actually mean less space for open-ended play. In some ways you might be better off with a simple metal toy car.”