THE SOLITUDE OF LATINX1

By Rocío Carlos

Associate Professor, Humanities and Sciences

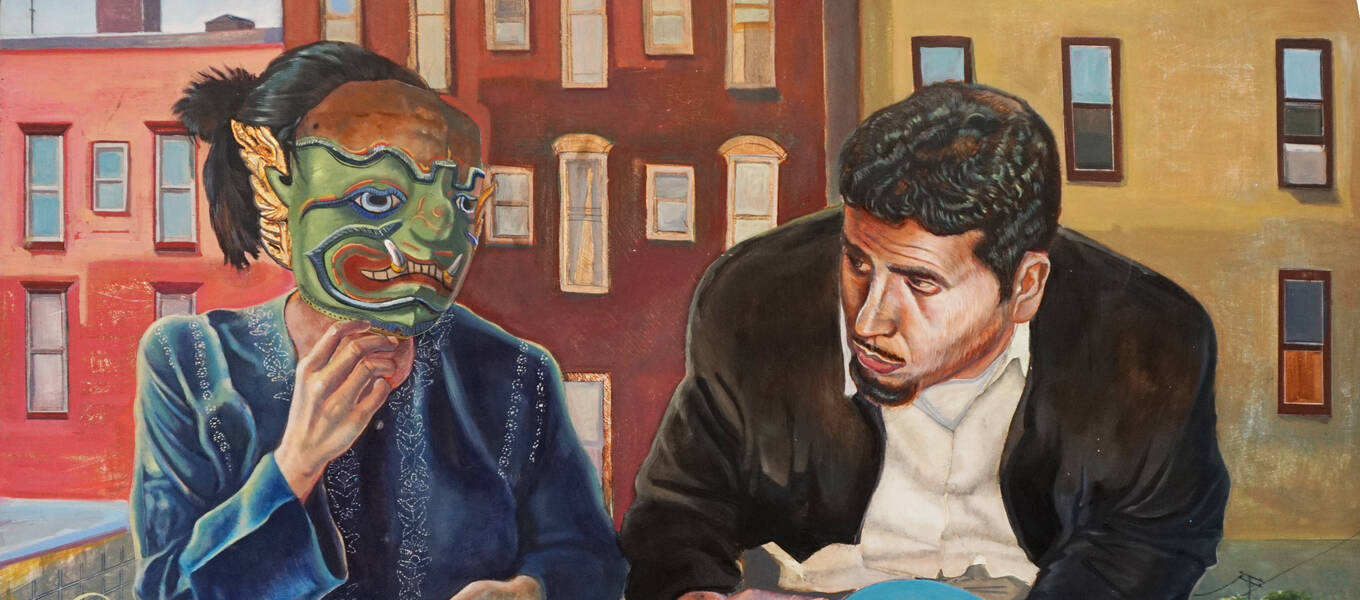

[Editor's Note: The following essay was originally published in a publication for IdentificarX, an exhibition that explores the complex and distinct contributions our Latina/e/o/x alumni have made to the field of art and design, and their significant cultural impact. The exhibition is on display from June 15 through August 23, 2024 at our South Campus Galleries.]

In an early meeting to discuss the title of the show which this essay attempts to contextualize, there was a lengthy and somewhat heated discussion of its name. Having used this term and related terms interchangeably for some time, and being an advocate of neologisms in general, but specifically when impacted groups attempt to promote visibility, I found myself lonely in my understanding of why, as off-putting (or even passé at this point) as it might be, LatinX must exist. The answer lies in its place between places, languages and generations. That no-mans-land often referred to as “ni de aqui, ni de alla,” an isolation captured often by writers and artists, and often overlooked or illegible to those outside of it. This solitude was famously alluded to by Gabriel García Márquez upon accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982 in a lecture entitled “The Solitude of Latin America.” It is fitting then, to begin this essay with an anecdote involving Gabo, an “erase una vez”2 for this show, and this generation. And so:

When Mario Vargas Llosa3 punched Gabriel García Márquez out, no one could agree completely on the motive, on who acted first, and on what role passion, delusion and pride played. It was not surprising, as La Malinche4, Sor Juana5 or Evita Perón6 could tell you, that a woman was blamed. What is certain is that, as with our histories, there would be instead conflicting accounts and legends that would spring up despite evidence, witnesses and survivors.

What I mean to begin with is the unreliability of documented history. To begin at our present predicament, of explaining ourselves yet again, at our vernacular innovations, I had to begin in the archive of collective memory. And memory is a hurricane7. What I mean to begin is a story in rebellion of linearity. There is no beginning, middle and end.

I’m reminded of the dusty town where my parents met, an ejido8 in the agricultural desert valley of Baja California, at the edge of the Río Colorado. Even now it is a place of incompleteness in search of an arrival. On the same block there is a single room of sticks that is burned to the ground, next to a giant stucco house with columns and flourishes, next to a modest Tetris game of unfinished cinder block rooms waiting for the next good harvest to progress. Or the next earthquake. Or the angry neighbor with the gun. And that word: Progress. The story of our survival in this hemisphere is the lived plot of Macondo9 and Comala10 again and again. Again the world ends, again we thrash in the wilderness, again the men with guns, again the river swells or dries, again the curiosity that we simply don’t die, and then they kill us, and then our names change, and then our tongues fork, and then we build, and burn, and build. And then we find that we were in a nation of ghosts the entire time.

01 Alternative titles include “Walter Mercado Predicted This” and “If You Know, You Know”

02 “Once Upon a Time”/ buckle up.

03 Peruvian author and Gabo’s frenemy.

04 Indigenous translator and scapegoat; often mythologized as the mother of Mexican mestizaje.

05 Criolla poet and intellectual, in trouble with the Marquis and the Bishop, for gay and nerd reasons.

06 Argentinian political figure, Broadway musical protagonist and Madonna cosplay.

07 María, Nicole and other novias of Bad Bunny.

08 Land back until it wasn’t.

09 A place the size of your misfortunes and also maybe Colombia?

10 The mouth of Hell; probably where Telemachus should have looked first.

And borders. I can’t even say the word without laughing. Instead, I’ll paraphrase Luis Valdez, founder of El Teatro Campesino: We never came to the United States. The United States came to us. And Malcolm X: We didn’t land on Plymouth Rock. The rock was landed on us. But in the hand-made calamity of history, what everyone remembers is arrivals. The Niña, Pinta and Santa María for example. And the amber waves of migrants, in makeshift rafts, in caravans, on the backs of beasts. Meaning trains11. What Borges calls a History of Infamy turned out to be our biggest survival tactic: making shit up: cleverness, inventiveness, innovation. As El Chapulín Colorado12 crowed: No contaban con mi astucia. They underestimated us.

Around 2017, five years after I began teaching at ArtCenter, I discovered the “ArtCenter at a Glance” page. I was looking for demographic information, for a reason I could arrive to teach my classes, attend meetings for faculty, even walk the halls and not see more than a half a handful of people like me. In a city that was certainly half Latino and where even the L.A. Times told me that the average person was like me: female, middle-aged and Latina. It was an irony that shook me: To have been born and raised in a region that literally used to be my parent’s country, to be surrounded by our cultures all of my childhood and now, outside my front door; to have been educated at the second largest public school system in the country and later the local public university, both which reported that nearly three quarters of the students they served were like me; to only now feel like an actual minority. I was floored to see a number that hovered and continues to hover at under 10 percent.

And I became curious about the demographic categories and wondered who thought to use them as they are, a sober reminder of racial caste categories13 imagined differently in Latin America and different regions of the U.S. as it expanded across the continent. Zero percent Native American. And what of the Tongva and Hahamog-na, here as borders moved and changed, as one colonizer’s language was switched out for another—how is it possible that where they still live and bear culture and witness, that they are not graduating from ArtCenter?

And true Los Angeles Natives aside, what are we, some of us far exceeding the U.S.’s complicated blood quantum requirements to use the term at all, but without connection or enrollment because where our families are from, there are no tribal rolls, only pueblos originarios and the project of Mestizaje, the nationbuilding exercise that erased entire family trees, cast its long and terrible shadow.The school reports one percent Black students enrolled. Appalling lack of diversity aside, could someone really think, someone who typed out those categories and got them approved and published them, that Black and Latino are mutually exclusive categories? This is the lingering concern beneath the idea of labels: the colonialist tendency to both taxonomize and uncomplicate. To make it easy, to not inconvenience or ask for too much. It was a maxim made for artists and innovators to break. And so here we are. Even from this position of outsideness, we obeyed the imperative of creativity: to paint on the walls of the city when the institutions are closed to us14 (see ASCO, JM Basquiat). To blend icons and mythologies when the storytellers and historians wrote us out of the book15 (see the city of El Monte).

To scavenge materials and make something new and bold (see Rascuache). And in language, to conjure entire lexicons of our own as we walk tightropes over never ending translation. For many of us, “Language” is far from being neutral terrain; it’s where we become visible to ourselves and each other. What some have called ‘switching’ for us is more like ‘stitching’—it’s refusing an “English only” mandate and insisting on normalizing hybrids like Spanglish and argots like Caló16, and even preserving our native words17 in resistance to a multifold colonialism. It’s one of the reasons I use the word Unitedstatisian. It’s a direct translation of the word Estandounidense, a word I heard all of my life for a person from the U.S. Not ‘American’— that referred to the continent, as Los Tigres Del Norte18 assert in “De America Yo Soy.” The name of this show, IdentificarX, is itself a kind of trap door. To enter an exhibition under this title is to wonder about language, about belonging, about geographies, histories and futures. What began in the 1950’s as a census list of “Spanish surnames,” in the 1970’s became the term “Hispanic,” arriving in the 1990’s as “Latino.” And at every step there have been conversations about who is included. Is there simply language in common? If so, what of the people dispossessed of any language besides English, over decades of real social consequences? There are people alive today who were punished in grade school for speaking Spanish. And what about Portuguese—are Brazilians not included? What about speakers of Creole, as in Belize? Geography presents another complication. Haiti is literally on the same Island as the Dominican Republic, yet except for baseball reasons19 are rarely included in the term. Nevermind that this requirement privileges the language of the colonizers, when our heritage languages are alive. Indigenous diversity language maps of Los Angeles are vivid with shading representing the numbers of speakers of K’iche, Zapoteco, Chinantecho, to name only a few. And consider regional custom and discourse. In places like New York and Miami, the vernacular “Latin” or “Spanish20” are perfectly acceptable as umbrella terms for the various nationalities and ethnicities which find that strange kinship of the Global South of the western hemisphere. Yet, a young Chicana spurning any bond with Europe would be baffled by such a word, or by the term “Hispanic,” as it invokes Spain as an origin point. And what of contraction and expansion of language—to hold all of us in order to increase our numbers, amplify our voices, our voting and consumer power, at the risk of erasing the most vulnerable, or naively assuming we have the same needs and concerns. Re-reading the catalogue of LACMA’s 2008 Phantom Sightings, it is notable that some of the artists selected by the curators bristled at the term “Chicano” as too niche or too political.

I remember my own father in the 90’s, annoyed at umbrella terms when he insisted “Mexican” was enough for him and that these “new” words were political gimmicks. What is for certain is that these terms function as demands for visibility, and what we who pay attention to language know, is that language is the opposite of precious, and resists the museum we insist it live inside. And so we reach a more recent notch in the rope: LatinX. LatinX is an attempt at interrogating gendered language defaults. This alone makes it a contentious term. The X refuses the ‘o’ or ‘a’ and the mandate to masculinize any collective noun containing even a single male identifier. It acknowledges the spectrum of gender possibilities. And most importantly, it was coined by those who are often railroaded by the racial harmony industrial project. Queer/ LGBTQIA+ (another set of identifiers with fans and haters) activists have always been called divisive when they demand inclusion and visibility as they labor inside of larger cultural recognition and civil rights movements.

11 La Bestia: A freight train migrants desperately cling through as it winds its way North. An allegory on wheels.

12 Simpson character inspo; wore tight pants before Nacho Libre.

13 Pinturas de Casta; a family album in period drag.

14 LACMA’s punk rock moment.

15 La historia no es como la pintan. Also covered wagon = Trojan horse.

16 Best known as “Pachuco” or Chicano slang. All you need to know

is the word Foo. Foo this and Foo that.

17 The only time to call guacamole “guac” is when it sucks.

As in “this guac is gwack.”

18 Mullet MVPs and accordion heroes.

19 La Serie del Caribe—a truer World Series?

20 “Feels too damn much like home when the Spanish babies cryyyyy”- Mimi, La Boheme of Nueva York

For those who enjoy the privilege of navigating life without their gender identity, expression or sexuality questioned or in some cases criminalized, the inconvenience of having to confront unexamined ideas is a hill to die on. And yet for those who innovated the term, it may well be a matter of life and death. I’m reminded of the double-paneled meme of The Simpsons’ Principal Skinner musing “Am I out of touch?” and then deadpanning, “No. It’s the children who are wrong.”

Despite the groanings of reluctant Latinos, The term LatinX can be found in more spaces, publications and government forms. Potentially, what usually happens will happen again: it will become so common that people will forget what came before, only to be annoyed when a new generation of youth yearning to belong bring forth a new term. And there is a twist: even as LatinX gains more legitimacy in the wider lexicon, there are critiques that again the U.S. is trying to set the tone for the entire hemisphere, that it favors a Unitedstatsian perspective of language. The X doesn’t always register in the rest of the continent, sounding sometimes like a Spanish J or an English H and in many indigenous languages as the sound “Shhh.” Our global southern cousins, then, have proposed “Latine’’ as a more natural sounding word. And yet, there is another question, circling above it all: why do we all have to have the same lexicon? Can it simply not be another regional feature?

The way some of us say tú and some of us say vos? And why does the X have to fit neatly into Spanish at all? Its “not fitting” may be the most accurate feature of all for generations of people displaced by destabilization, violence, or borders that simply moved over them. The X, its strangeness, fits our strangeness, our es-tranged-ness, countries or languages away from our people’s origin stories. So we have made our own stories, and lexicons. We shrug off words like “Pocho” and “No Sabo21” and their allegations of ignorance, of forgetting or scornings one’s heritage. Perhaps we simply decline aspirational appeals to respectability and assimilation by all using the same term, even as language purists scoff at our shiny inventions. We cobble together neologisms and new conjugations to soothe ourselves and laugh together. And If queerness has taught me anything, it’s that acceptance is a moving target; just when you think you’ve attained it, it’s behind a new door, and someone else is holding the key.

Potentially, even a show like IdentificarX may be a bittersweet arrival for some of the artists; a surprising visibility after years of walking unknown or misunderstood through the halls of the school. LatinX students find in ArtCenter a new “no-man’s-land.” A vacuum of LatinX culture in the middle of a LatinX cultural hub. This new generation of students is no longer content to be let into an institution of great prestige, only to find that the curriculum and its proliferators largely exclude makers, traditions, entire histories of arts and literature from countries below the U.S.-Mexico border, let alone from the diaspora communities within the U.S. that they themselves be a part of. They form “whisper networks,” renegade social media accounts and flock to the few courses which may not be required but do make them feel seen. They create safe spaces for each other, while the institution takes its time to include them. On top of the usual stresses of succeeding as students and growing as artists, LatinX students experience loneliness of being invisible in plain sight, and the absence of spaces in which to discuss topics like the very one this essay attempts to wrangle.

If you’re seeing this show in 2024, you’re likely looking at something different than what this essay addressed initially. The premise of the show remains the same: to bring together the works of many of ArtCenter’s LatinX alumni. To create visibility and celebrate the careers of these artists and designers, many who were secured by the organizers and curators of the show over many months of building trust and forging relationships. This work cannot be underestimated. Often when we visit an exhibition, the labor and research which built it are an invisible scaffolding, but in this case, removing it divorces the show, and the works exhibited from a certain context. Many of the organizers, themselves practicing and successful artists and mentors in their respective fields, brought to us the works of these alumni through their reputations in their communities, studio visits, long email chains and heartfelt conversations.

As with the participants in that formative LACMA show over ten years ago, some were curious about the term LatinX, others hesitant to gather under its banner. Still others were reluctant to align themselves with ArtCenter at all, recalling the experiences of invisibility even as they learned valuable skills and techniques. This illuminates the unresolved struggle of communities of color inside the exhibition and educational spaces which past generations fought so hard to open to us: a diasporic solitude. The isolation of being few in number as students, or with few mentors and experts with contextual knowledge to guide them, of knowing that there has to be some value in the histories and art and design traditions and vibrant contemporary movements of the places their families come from, but which never comes up in curriculum22. In 2024 this should certainly change, and the mounting of this exhibition must be a step in the institution facing itself and its role in the solitude of students who work to make their visions a reality.

I’ll end with the words of Gabriel García Márquez: "In spite of this, to oppression, plundering and abandonment, we respond with life. Neither floods nor plagues, famines nor cataclysms, nor even the eternal wars of century upon century, have been able to subdue the persistent advantage of life over death."

21 A living J-Lo meme (mi gente LatinO); el cringe.

22 Rooms of silence across the AICAD landscape.

Rocío Carlos was born and raised in Tovaangar/Los Ángeles. She is the author of (the other house) (The Accomplices/Civil Coping Mechanisms), Attendance (The Operating System) and A Universal History of Infamy: Those of This America (LACMA/Golden Spike Press). Carlos often collaborates with visual artists and her work has found its way into exhibitions at LACMA, Ave. 50 Studios, the L.A. County Library, The ONE Archive Foundation’s Pride Publics. Her poems have appeared in Chaparral, Angel City Review, The Spiral Orb and Cultural Weekly. She lives in a bee-infested house in the chaparral with her partner and cats. She is a teacher of the language arts and her favorite trees are the olmo (elm) and aliso (sycamore).