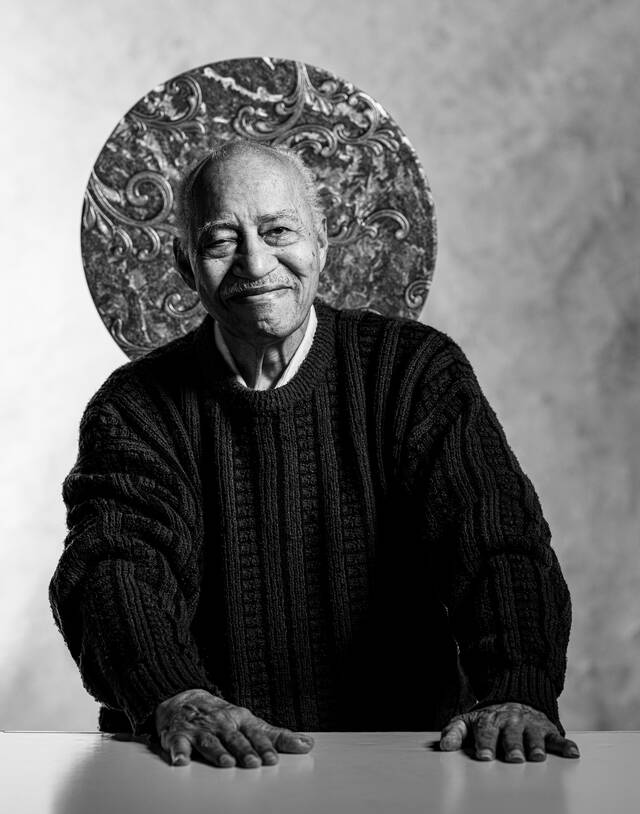

Emerson Terry

Emerson Terry is an accomplished illustrator who came up through the advertising ranks in the 1950s when there were very few African Americans in the field.

Elizabeth Bayne: How did you find out about ArtCenter?

Emerson Terry (BFA 54 Illustration): I was going to Los Angeles City College. I had just gotten out of the service. A friend of mine took me to ArtCenter, which was over on 3rd Street at the time. When I finished looking through the halls at the student work, I said, "I've got to get into this place." I made a few samples of my work, took them out to ArtCenter, and they accepted me. I was a veteran of World War II and I had a GI bill, so the GI bill I think was what got me in.

EB: What was your experience like at ArtCenter?

ET: It was a good experience, a wonderful experience as matter of fact. When I was supposed to graduate, they told me I couldn't because I changed my major in the first semester. I wanted to be an illustrator and they had me in advertising design. I had to do a whole new semester. No money, no GI bill. I worked at Douglas Aircraft at night and North American Aircraft during the day. I made enough money to go back to school, and I finished the ArtCenter in 1954. I was supposed to finish in '53.

EB: What was it like working in advertising and illustration at that time?

ET: Racism in 1954 was almost as bad as the early days. When I graduated from ArtCenter, I took my portfolio with all my samples in it, and started knocking on doors. I could not get in. I worked for a big agency out of Chicago. I got in at the very bottom of the loop. Some other students that came along at the same time got in as junior art directors, junior illustrators. But for me, I did all of the dirt, the cheap stuff, anything that anybody else didn't want to do — change the water for the top illustrator in the jugs they used to clean the brushes in and stuff like that — and occasionally get a small piece of artwork to do as an illustrator.

About the Series

In ArtCenter's 90-year history there have only been approximately 300 Black alumni. Impact 90/300, a documentary by Elizabeth Gray Bayne, profiles 25 of them. This series revisits each interview from the film, originally created for ArtCenter DTLA's 90/300 Exhibition.

Whether you liked it or not, you had to keep on pushing.

Emerson TerryBFA 54 Illustration

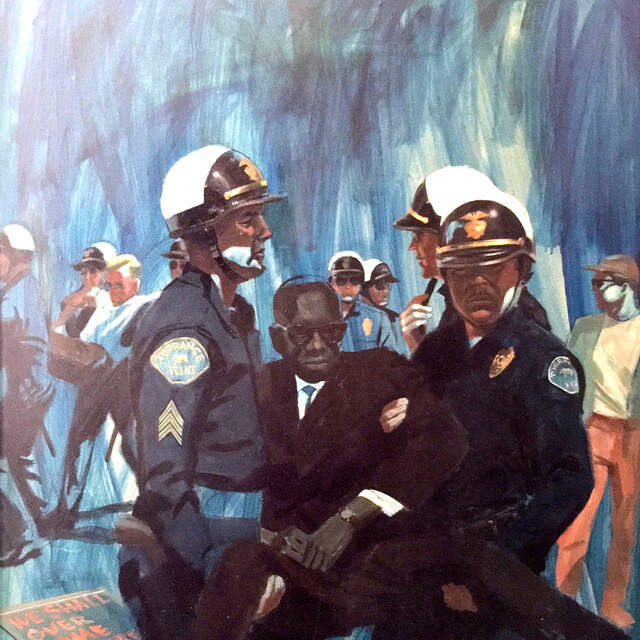

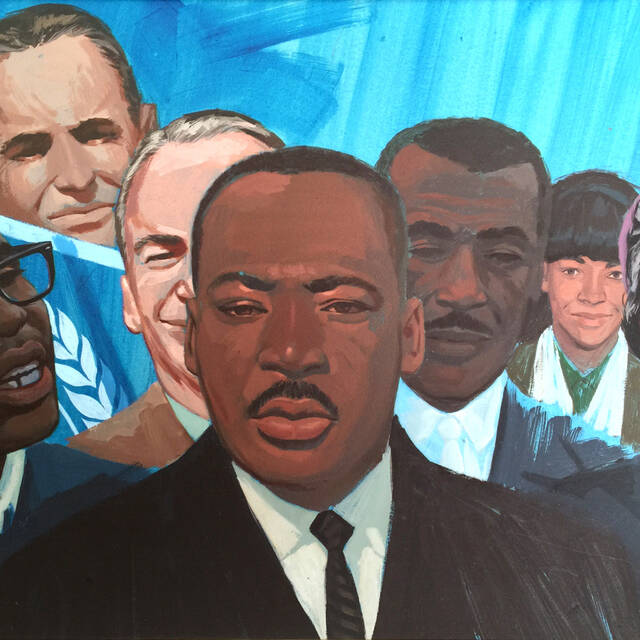

Selected Works

From Words to Action

ArtCenter's Commitment to Black Lives

EB: As an African American, what was it like breaking into the industry?

ET: I expected to have problems with racists, with people who would not give you the time of day. But also there were people who were decent enough to give you work, and some of the students that I had gone to school with became art directors and they gave me work. I think at the time there was a song out by an African American group that said, "Keep on pushing." Well, that's what we had to do. Whether you liked it or not, you had to keep on pushing.

EB: You had to jump through a lot of hoops — have you seen much change?

ET: Oh, lots of changes, but not enough. While I was at General Dynamics, one of my daughters was in elementary school, she did a paper about the Black cowboys. And the teacher told her, there was no such thing as Black cowboys. What? I had given my daughter a book on Black cowboys, I like to call them African cowboys.

I made the first painting about the African cowboys. Then a second painting, and before long, I had a series of documentary paintings. A friend of one of my daughters was working for the L.A. Times, and he wanted to know if he could do an article on it.

Then every television station in Los Angeles came out, radio stations, schools and places like that. And all of a sudden we were having an exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry, and the whole thing became a huge exhibit.

EB: How does that speak to the power of art and the power of training other Black artists to utilize their skill sets?

ET: Our history is so important. And consequently, as an artist, I needed to take my art and use it as well as I could to tell our history. I felt that if I could document the Air Force history, I sure ought to be able to document some of our history.

EB: You're 94. ArtCenter is 90 years old, and during that time, there have only been 300 black alumni. Is that a good number? Has that come a long way since you were here in the '50s?

ET: I have a saying, Hindsight is 20-20. Foresight is blind. And what I mean by that is we can't tell what the future's going to be. I think that even I have made progress, and you guys coming along today are going to make even more progress. As a matter of fact, you’ve got to do like they said in the song, keep on pushing. And we will do better, I hope. I believe.

*This interview was edited for brevity and clarity.

Photo credit: Everard Williams