Adapt or Die

Generative AI is poised to alter the creative landscape forever. What does it mean for artists and designers?

In the 1992 Star Trek: The Next Generation episode “Schisms,” several crew members of the Enterprise share a vague memory of awakening in the middle of the night atop a table. To get to the bottom of this mystery, they gather in the holodeck, a space in which the computer can render objects, individuals and environments as lifelike, 3D holograms. Like a forensic sketch artist, the computer builds the crew’s recollections in real time as each person adds new details:

“Computer, decrease the table’s surface area by 20% and incline the top 15 degrees.”

“Make this a metal table. Lower the surrounding light level.”

“Computer, give me a bright light right above the table. An overhead lamp.”

“Create a metal swing-arm. Double-jointed. Total length: one meter.”

“Computer, produce a pair of scissors attached to the armature.”

“There were noises coming from the darkness, strange, like whispering.”

Thirty years after the airing of that episode, Lynda.com co-founder and ArtCenter Trustee Bruce Heavin (BFA 93) addressed the College’s Fall 2022 graduating class at the Pasadena Convention Center.

“This was adapt or die time,” said the artist and entrepreneur, recalling the disruption experienced in the worlds of graphic design and photography in the early 1990s as a result of software such as QuarkXPress, Corel Draw and Adobe Photoshop. “It didn’t take much for some [art directors] to feel displaced. A lot of them considered retiring. Some adapted to the computers with a renewed sense of enthusiasm.”

Heavin never used the term “AI” in his presentation—he didn’t need to. The parallels to today’s uncertainty, due to the rise of text-to-image generative AI programs, was lost on no one.

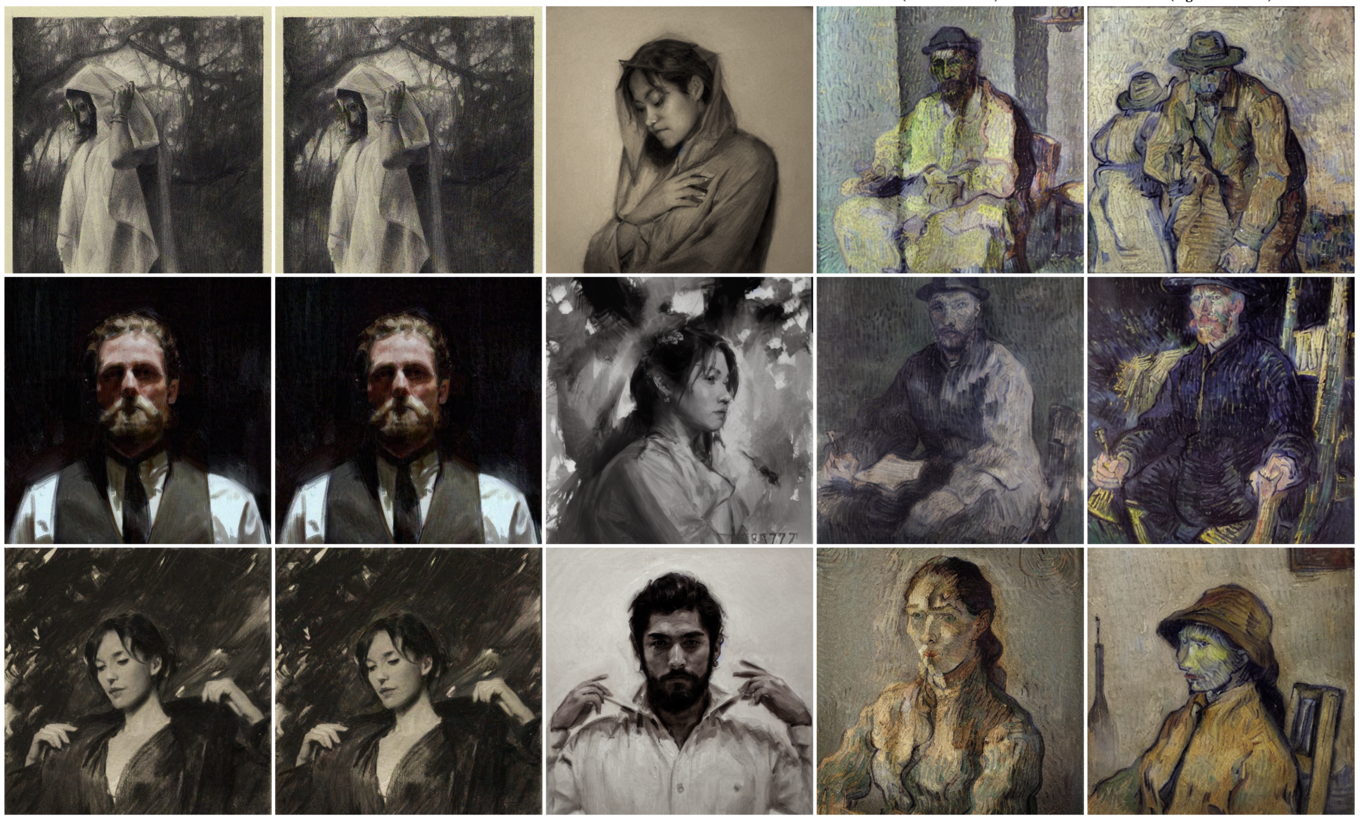

Just three months prior, game designer Jason Allen made headlines by entering AI-generated artwork in the Colorado State Fair and winning first place. Shortly after that, the Internet was abuzz with works generated by AI programs like Midjourney, DALL-E and Stable Diffusion. Social media overflowed with selfies that were transformed via AI into painterly portraits. The San Francisco Ballet caught flack for using AI-generated artwork to promote its annual performance of The Nutcracker. And artist Johnny Darrell employed AI to imagine how the film Tron would have looked had it been directed by surrealist Alejandro Jodorowsky.

One of my students said, 'You have lots of experience, so you know what you're doing. But I feel like I shouldn't be working with AI yet.' They're coming to ArtCenter to learn the skills, the craft, the thinking, the terminology.

Gerardo Herrera (BFA 91)Associate Chair, Brand Design and Strategy

ArtCenter College of Design

“Every night I’m working on leveling up my skills, and I feel like if I stop, the train is going to go by,” says Gerardo Herrera (BFA 91), associate chair of ArtCenter's Brand Design and Strategy MDes program and the director of brand experience at Design Studio Nuovo. Herrera has spent the past 11 months diving headfirst into AI and passing his newfound knowledge on to his students. Though no stranger to the fast-paced tech world (he's worked for over 15 years with outfits like Nokia and Samsung), he feels today's pace of change is unprecedented.

As the former director of packaging in the Graphic Design program, Herrera made it his goal to fully understand the applications and implications of AI in his arena. The AI-generated designs and workflows he has shared with his upper term students include packaging concepts he created for octopus-infused olive oil, fly fishing gear and high-end tequila. In turn, his students have used AI programs to create packaging concepts for projects ranging from an educational card game for the Dublin Zoo to a Hawaii-inspired tropical juice.

Herrera recalls receiving some insightful feedback when he first began introducing AI to his classes. “One of my students said, ‘You have lots of experience, so you know what you’re doing. But I feel like I shouldn’t be working with [AI] yet,’” says Herrera. “They’re coming to ArtCenter to learn the skills, the craft, the thinking, the terminology.”

In other words, he says, they need to know their stuff backward and forward so that when they’re telling somebody else—or something else—what to create, they’ll know what they’re looking for.

Herrera says the current moment reminds him of the arrival of the Mac computer. “I told my students how, back in the old days, I would tell the typesetter how to set the type, the point size, the tracking, the word count,” says Herrera. “Then, when the Mac showed up, everybody became a typesetter. However, because I understood that language, when I sit down at my computer, I know exactly what I want when I’m using the interface.”

AI takes the pain out of failing. You can fail 10 times a day, 100 times a day — it’s no big deal. All those crazy ideas you have, you can test them out in ways that you’ve never been able to do before.

Sho Rust (BFA 15)Founder and CEO

SHO.ai

Sho Rust (BFA 15) is founder and CEO of the Missouri-based company SHO.ai, which helps organizations such as branding firm Labbrand, public radio station WETA and Rust’s alma mater, ArtCenter, incorporate AI into their workflows. “Something people underestimate is how much better experts are at using these tools than nonexperts,” Rust says. “Give a kid a hammer, and he’s not going to build a house.”

He remembers the excitement he felt back in 2015 when research laboratory OpenAI, maker of ChatGPT and DALL-E, announced it would make its research open to the public. “That was a beautiful thing, because now anybody could have access to their [large language] models,” says Rust, who was working for consulting firm BCG Digital Ventures at the time. “Previously, those models were exclusive to big tech companies, which made it hard for anybody else to compete.”

He continues,“Once I started digging into OpenAI’s research, it quickly became clear to me that [AI] was the future.” In 2018, when the first version of GPT came out, he had an epiphany of sorts: “I decided that either this technology was going to replace me, or I could turn it into a tool that people like me could use.”

Rust created a few prototypes that were promising enough that several of his friends and colleagues decided to leave their gigs at the time to follow him into this new arena. “I convinced really smart people from all over the world—from Venice Beach to New York to Paris—to move to Missouri and work out of my grandma’s garage for a year,” he says, with a laugh.

One thing his team figured out quickly was that the quality of the AI’s output was dictated by the quality of the data input: “We learned we needed really good, quality data, and a management system so that companies could train and create their own AI models.”

Rust and Herrera recently co-taught a seven-week generative design workshop with Brand Design and Strategy's MDes lead professor of systems design, Christian Saclier, who also serves as PepsiCo’s vice president of design innovation. In that workshop, Rust showed students how AI programs, when supplied with detailed client information (e.g., a company’s mission, core values, history), can create very specific and personalized outcomes.

“Their output was amazing across the board,” says Rust, adding that one of the things that excited him most about the course was seeing how the AI gave the students “superpowers” when it came to the iterative aspect of the creative process. “AI takes the pain out of failing,” he says. “You can fail 10 times a day, 100 times a day—it’s no big deal. All those crazy ideas you have, you can test them out in ways that you’ve never been able to do before.”

There’s a lot of potential with AI when it comes to the fields of science and medicine. But human creativity is not a problem that needed to be solved. Generative AI is actively filling the role of an artist. It’s straight-up job replacement.

Rachel Meinerding

Co-founder

Concept Art Association

But exactly how generative AI programs unleash those superpowers is a bone of contention among some artists and designers, because these programs were trained with art and design harvested from the Internet—work created by human beings who were not credited or compensated by the companies creating the AI programs.

For Rachel Meinerding, co-founder of artists’ rights advocacy group Concept Art Association, this leads to one conclusion: AI-generated artwork, in its current state, is unethical. This past May, Meinerding spent time lobbying in Washington, D.C., making that case. Though not a concept artist herself, Meinerding is married to ArtCenter alum Ryan Meinerding, who heads up the visual development department at Marvel Studios.

“Ours is not an anti-tech attitude, as there’s a lot of potential with AI when it comes to the fields of science and medicine,” she says. “But human creativity is not a problem that needed to be solved. And what generative AI is doing in the creative field is actively filling the role of an artist. It’s straight-up job replacement.”

Meinerding points to a recent Goldman Sachs study that estimates up to 300 million jobs worldwide could be lost due to generative AI programs. And she’s quick to push against the narrative that AI is actually democratizing art. “Yes, there are people who make a good living from being professional artists, but ‘the starving artist’ is a trope for a reason,” says Meinerding, adding that most people become artists not to strike it rich, but because it’s their passion. “A lot of working-class and middle-class people could end up losing their jobs,” she says.

Despite her concerns, Meinerding is hopeful for the future. She feels fortunate that the Concept Art Association began advocating so early in the discussion, and she’s grateful that donations from members have made it possible for the organization to lobby in D.C. “It’s encouraging,” she says. “It shows how much this is affecting the community and how much people want their voices to be heard.”

Also encouraging for Meinerding, when it comes to lobbying, is that intellectual property is a concept that U.S. lawmakers historically are eager to protect.

Sarah Conley Odenkirk, a partner at Cowan, Debaets, Abrahams & Sheppard LLP, specializes in art law and has a clientele that includes artists, digital platforms, arts organizations and creative innovators. “If your business model is being built on the raw material of other people without any concerns as to whether that material is protected or not, you’re building a commercial venture on the backs of artists,” she says. “That’s not okay ethically or legally.”

But what is and isn’t ethical or legal when it comes to AI is not always straightforward.

Odenkirk points to a Februrary 2023 decision by the U.S. Copyright Office, reversing its 2022 registration of copyright to Kris Kashtanova for their comic book that included images generated by Midjourney. After learning more about how Midjourney creates its imagery, the office determined that the structure and the text of the comic book could be copyrighted, but the imagery could not. “The copyright office has long held that only humans can own copyrights,” says Odenkirk. “Machines, animals, anything nonhuman may not own a copyright.”

In January of this year, artists Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan and Karla Ortiz filed a class-action lawsuit against Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and DeviantArt, calling those companies’ AI image generators “21st century collage tools that violate the rights of millions of artists.” The suit calls out how users of those programs enter into their prompt the words “in the style of,” followed by a specific artist’s name, in order to convincingly produce art in that artist’s style. However, “in the U.S., artistic style is not protected,” says Odenkirk.

Further complicating matters is that in 2022, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit held that simply removing metadata from an image was not enough to prove copyright infringement is intended, making it harder to prove that a company that strips metadata from an image before using it to train an AI program is in the wrong. “Eventually, we may have guidelines and regulations concerning how materials are gathered by AI companies,” says Odenkirk. “We may see obligations being placed on those companies to make sure their data sets are ‘clean,’ meaning they're bringing in material that's been properly licensed and is properly attributed.”

Until that day arrives, artists may need to find other solutions to protect their works.

If your business model is being built on the raw material of other people without any concern as to whether that material is protected or not, you’re building a commercial venture on the backs of artists. That’s not okay ethically or legally.

Sarah Conley Odenkirk

Partner

Cowan, Debaets, Abrahams & Sheppard LLP

“This is a really critical time right now,” says Ben Zhao, a professor of computer science at the University of Chicago who, along with his graduate students in SAND Lab (Security, Algorithms, Networking and Data), developed a program to help artists protect their work. “In the next few months, we could see dramatic changes for the future,” he says.

Last October, Zhao was invited to a large town hall in which hundreds of artists explained to him the existential threat they felt generative AI posed to their industry and their livelihoods. The artists wanted to know whether a facial recognition protection program Zhao and his team had developed could be used to prevent AI programs from mimicking their individual styles. After investigating the matter, Zhao and his students got to work, and the result was Glaze.

As Zhao explains it, when an artwork is processed through Glaze, the effects it adds to the image have a minimal impact on how humans perceive the work. But if AI tries to use that same image to learn and reproduce the artist’s style, it faces a number of distortion barriers, and it can even be tricked into creating a work in a completely different style (cubism, for example). “The Glaze effects are robust and can’t be circumvented,” says Zhao. “They are computed on a pixel level, so they’re fully integrated with the image. You can try all the normal things—change the image’s format, resample it, take a screenshot, etc.—the effects remain.”

Teaching students about AI’s abilities and limitations is something ArtCenter's Interaction Design Chair Todd Masilko (BS 96) and Associate Chair Jenny Rodenhouse (MFA 15) have done for seven years in AI and Agents. The duo, along with former chair Maggie Hendrie, now a dean overseeing Interaction Design and other programs, created the course after noticing a trend emerging during assessments with graduating students. Masilko says, “Our students are very detail- and process-oriented, and yet, when discussing their portfolio, they’d get to a part of a project that involves AI and say, ‘And then this happens, because of AI.’ It was apparent that AI was equal to magic.”

He continues, “A mobile app proposal wouldn’t make it through a class without a discussion of whether it was technically implementable on a phone. So we decided students needed a course where they were actually making projects with the medium—a place where they could understand AI’s capabilities based on the way it actually works.”

In the first few weeks of AI and Agents, students get their hands dirty with a variety of AI programs, which, Rodenhouse says, helps fuel later classroom discussions that counter what the students may have learned about AI through popular media. For example, she says, just understanding how an AI program recognizes visual objects is more complex than many think: “If you want an AI program to know cat, it doesn’t understand cat. It can understand certain patterning of light and shadow in cat imagery, but that’s all the program can replicate.”

She adds, “That’s part of the challenge of working with emerging tech—there’s the promise, the ‘hope’ narrative, and then there’s what the technology is actually capable of doing.” The key, she says, is for students to discover those limitations for themselves. “We’re not demystifying it—by engaging with the medium, the students are demystifying it for themselves. And once they understand how it works, that’s where they discover the really rich opportunities.”

By engaging with the medium, the students are demystifying it for themselves. And once they understand how it works, that’s where they discover the really rich opportunities.

Jenny Rodenhouse (MFA 15)

Associate Chair, Interaction Design BS

ArtCenter College of Design

One example Rodenhouse and Masilko point to is a 2020 student project called Arter, by now-alums Rodney Edwards (BS 21) and Siladitiyaa Sharma (BS 20). The two are currently full-time product designers at Microsoft and Meta, respectively. Three years before ChatGPT, Midjourney and the like started making headlines, Arter presented a concept for a tool that would assist design teams with the storyboarding process for client presentations.

Via a deceptively simple UI, users interact with a “shape-shifting AI Assistant” named Art, whose role it is to make the user feel like an art director. A video explaining the process shows a user typing the words “A person sitting in a café working on their laptop, drinking coffee.” The program then highlights verbs and nouns from the sentence. When the user drags the word “person” into a blank square, a simple 3D model of a person appears in the square, and Art then prompts the user for more details: “I see you dragged your first object into the scene to sketch. Fancy! Tell me a little bit more about what the sketch of the person should look like.”

The project went on to win multiple awards, including Gold at Muse Design Awards 2020, Silver and Bronze at International Design Awards and a Best Case Study at Bestfolio. Many people were convinced it was an actual product. “People were asking us, ‘Is this a startup? Can you build it?’” says Rodenhouse. “It would have cost us millions just for the data to train it.” Adds Masilko, “But right now, it would be the perfect VC-backed startup.”

ArtCenter Trustee Bill Gross, founder of tech incubator Idealab, likens the rapid advancement of generative AI—"where a computer can take a trillion words and a trillion images and synthesize them in a nano-second”—to the meteorite that struck the Earth and wiped out the dinosaurs. Just like that meteorite, generative AI is a disruptive event, he says.

“New animals, including humans, evolved from that explosion,” says Gross, who believes AI is the biggest technological advancement since the advent of Netscape Navigator in the mid-’90s. “AI is an explosion of new opportunities. And just like when that meteor struck, right now there are lots of clouds overhead. Will there be some bad actors? Yes, for sure. But there’s also a lot of new scurrying around happening and new beautiful things that will emerge.”

Editor's note: This article was originally printed on July 13, 2023. To coincide with the print version of this article, this story was updated on September 22, 2023, and again on September 26, 2023. Most changes were minor and grammatical in nature, with the exception of the job titles for Maggie Hendrie, Gerardo Herrera, Todd Masilko and Jenny Rodenhouse, which have been updated to reflect changes at the College since the original publishing date.

Related

feature