Sustainability Studio

By moving our mindset from "how can we be less bad?" to "how can we be 100 percent good?" students redesign a variety of objects and environments to meet current needs without compromising the potential for future generations to adapt these same strategies to meet theirs. To this end, students analyze existing products, environments and processes for sustainability and implement intelligent design strategies to reduce our ecological footprint.

Interview with Instructor James Meraz

ArtCenter: How would you describe the class to a prospective student?

James Meraz: I try to push the boundaries in how we think about sustainable design and create sustainable futures. Students look at the materiality of a given project, where and how it's sourced and whether it's upcycled, recycled or invented. We also look at a systems approach, which has us considering context, energy sources and passive vs. active technologies. The last component is experiential, creating strong narratives and experiences that has the user considering, and perhaps re-thinking, our relationship to our natural resources.

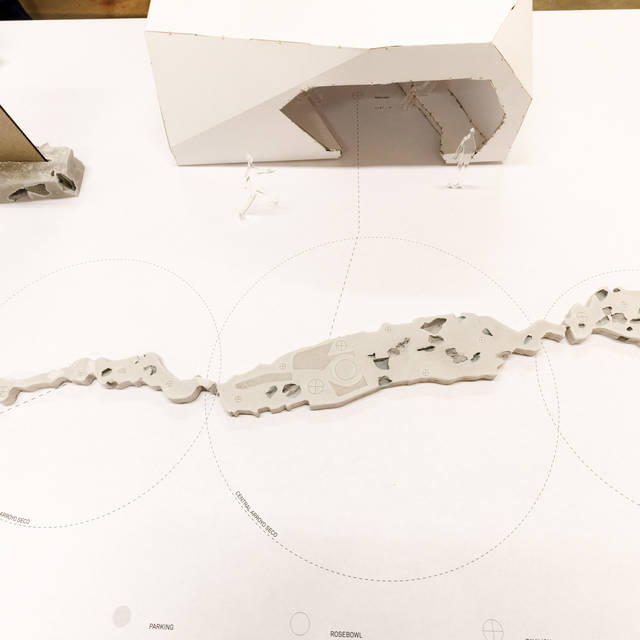

Sustainability Studio: Reimagining the Arroyo Seco

What I valued most about this course was the extreme exposure to nature I had in the deep forests of Costa Rica. My experience there taught me to be more than a student, it taught me to be an explorer, a nurturer and a survivor.

Adriana AvendanoEnvironmental Design

AC: What are some of the objects that are redesigned during the course?

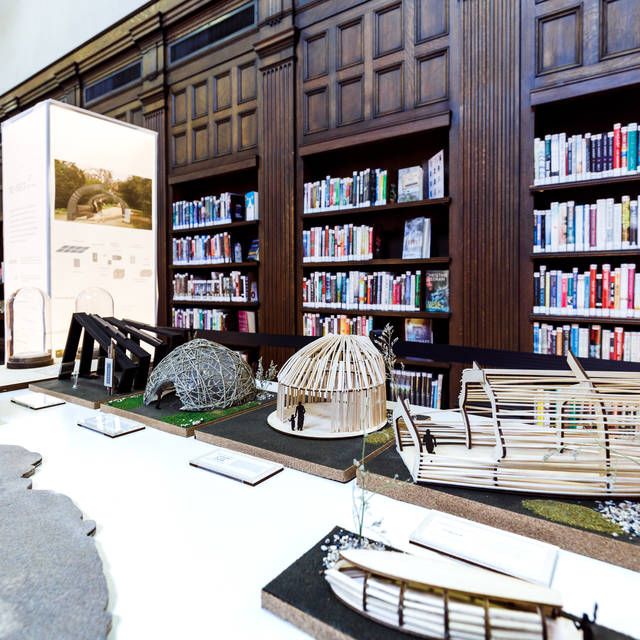

JM: We’re always exploring different contexts. One term we’ll examine space in the public domain — from pocket parks in the urban environment, to pre-fab modular systems for emergency situations. Currently, we're looking at creating bridge housing on city-owned lots for those who can't afford housing in Los Angeles.

AC: What inspired the direction you took with the curriculum for this class?

JM: A serious passion of mine has been to create experiences that have students literally and physically attuned to nature. In the classroom and the creative community, there's a lot of dialogue about sustainability, yet our most utilized source of intelligence is the Internet. This lead me to create Eco Research Lab, which explores biologically intensive environments, like the central rainforest of Costa Rica. By studying nature's intelligence, behavior and performance, we emulate nature's phenomena and attributes to solve design challenges.

AC: What are some of the most important concepts and ideas you hope students take away from the experience/classwork?

JM: By focusing on our precious natural resources, students create design solutions that not only elevate the human condition, but have us living in a symbiotic relationship with nature.

AC: What are some of the assignments and materials you've incorporated into the curriculum that you hope will encourage and provoke students to challenge themselves and break new ground creatively?

JM: A key stepping stone to achieving a sustainable practice is to design products that will disassemble easily at the end of their useful lives. Through the hands-on "de-construct" project, students select an iconic industrial design product or object from a particular era and de-construct and catalogue every component, material and screw. Most products are designed to be put together, not come apart in a useful or sustainable way. The exercise challenges our disposable culture by exposing what is destined for landfills.