Eco-Imaginaries

In this intensive, project-based course, students focus on emerging topics that ladder up to Media Design Practices’ research interests, from technology to science to global politics.

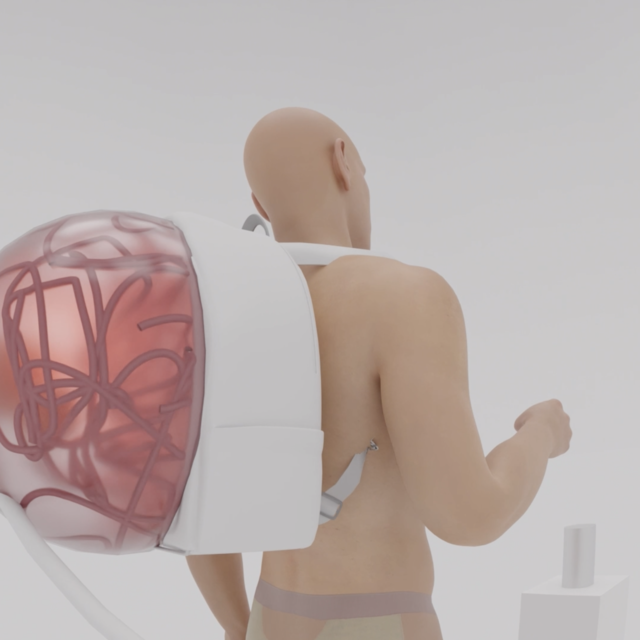

With the obvious urgency for humans to re-evaluate our relationships with the planet, the theme for this term was nature. The incredible outcomes ranged from plug-and-play vital organs to robot pets uploaded with the behaviors of a lost family dog.

Interview with Instructors Tim Durfee and Mashinka Firunts Hakopian:

ArtCenter: How would you describe this class to a prospective student?

Tim Durfee: Eco-Imaginaries explores alternate relationships we, as humans, might have to what is generally understood as nature.

Mashinka Firunts Hakopian: A space for fostering critical ecological imaginaries. An invitation to envision and design relationships between human and nonhuman organisms — and their surrounding environments — that depart from prevailing models.

Image Credit

Leslie Ho, Cohabitation Proliferation

Related Links

Student Work: Eco-Imaginaries

I found designing a narrative and aesthetics informed by theories very valuable. It taught me the importance of thinking critically in design, especially considering ecologies in the future.

Mary ZhangStudent, Media Design Practices

AC: What are some of the most important concepts and ideas you hope students take away from the experience/classwork?

TD: To be an effective and responsible designer, one’s potential responses to a given condition must not only be expansive, but one must also be willing to question what those given conditions are assumed to be. When it comes to the many ecological crises we face today, it is not good enough to merely “solve for x,” because all variables of the equation are in need of re-evaluation and change.

MFH: One core intervention of the course was to dispel techno-solutionism as a response to ecological crises. Instead, we turned our attention to longstanding practices of living ethically with land and ecologies. For example, we considered the model of “Indigenizing the Anthropocene” proposed by Zoe Todd, a Métis anthropologist and scholar of Indigenous studies. We also looked to work by Charles Sepulveda, a Tongva and Acjachemen scholar whose work focuses on California’s histories, who has proposed “Kuuyam” (a Tongva word for guests) as a decolonial model that “ prioritizes sacred human relationships with land and water.”

AC: What inspired the direction you took with the curriculum for this class?

TD: The Media Design Practices MFA program has a sequence of studios leading up to the thesis year, each one focusing different design modes, methods and topics. For this particular studio, we take on an intentionally vast subject, coordinate a series of encounters with experts and engage in a process of question-finding.

The goal is to produce a project that is a type of alternate brief, rather than a solution, related to a familiar subject. Last year, we focused on Work, so we thought a similarly unwieldy theme for this year could be Nature. There is an obvious urgency for humans to re-evaluate our relationships to (and our responses to) our concepts of the natural, and we were excited by the challenge, so we hit “send” on the idea.

MFH: Much of the course design was structured around highlighting recent experiments in eco-aesthetic output, exploring the ways in which artists, designers and makers have a vital role to play in blueprinting critical ecological imaginaries. To that end, the course featured guest speakers and colloquia that included talks by Joel Garcia, Aroussiak Gabrielian, Yasaman Sheri, Caitlin Berrigan, Jennifer Liu, Tega Brain and Stuart Candy.

AC: What are the assignments and materials that challenge students to break new ground creatively?

TD: In the studio section, students started by collecting key materials around a topic falling under one of three sub-themes related to the human-to-nature relationship today: Climate (existential), the Post-Human (epistemological), and Synthetic Biology (ontological).

Then, after a process of identifying questions, unresolved issues and under-considered implications present in the research, they each developed specific scenarios to present novel visions depicting how humans might exist differently with non-humans, with the environment, or even with their own bodies in the near-future. It was important that this work prompt active discussion – as opposed to operating as idle illustration — so we welcomed approaches that were sometimes absurd, or contradictory, or even patently undesirable.

Focused workshops by our teaching associate Zane Mechem introduced students to advanced creative techniques to support the production of their final short film.

MFH: The seminar portion of the course was organized according to some of the key discourses in recent eco-criticism. Our topics included Indigenizing eco-futures, multi-species entanglements, synthetic ecologies and eco-feminisms. Each of the seminar meetings included discussions of core readings, as well as flash workshops that invited students to explore key concepts from the readings through brief, in-class making experiments.

For example, one flash workshop asked participants to develop a visual (a sketch, blueprint, an AI-generated image, etc.) of a multi-species wearable that incorporates Anna Tsing’s ideas of multispecies entanglement. This workshop asked students to reflect on the question: “What would a wearable look like that encourages the wearer to recognize themselves as entangled with the surrounding environment?”

AC: What were some of the most interesting/surprising ways the students responded to the challenges and assignments?

TD: Most projects opened up interesting conversations. Yet, it's actually the exuberant variety and productive weirdness of the approaches when listed together that best captures the spirit of the studio:

- Plug-and-play vital organs one can buy on a retail shelf

- Island habitats for non-humans, formed from plastic waste

- Large methane-mitigating stomachs for the home

- Hiking that accelerates, rather than inhibits, rewilding

- Mitten-like wearable tongues for tasting without ingesting

- Vertical urban pickling networks

- A fungal decomposition promoter as an end-of-life wearable

- Removing dams to live-with, rather than control, waterways

- Human burial that enables coral restoration

- Living with ancient time-released viruses from melting polar ice caps

- A world where humans and plants exist in literal daily entanglement

- A photosynthetic patch for humans

- An urban lung for public aspiration

- Eco-system-enhancing mesh-networks for forests

- Restaurants that serve only invasive species

- Robot pets uploaded with the behaviors of a deceased family dog

- Sacred desert-dwelling spore-rooting boars to mitigate Valley Fever

Philip van Allen

Phil van Allen is an interaction designer whose work ranges from the practical to the speculative. In the past, he has been a recording engineer, software developer, digital studio founder, and researcher.