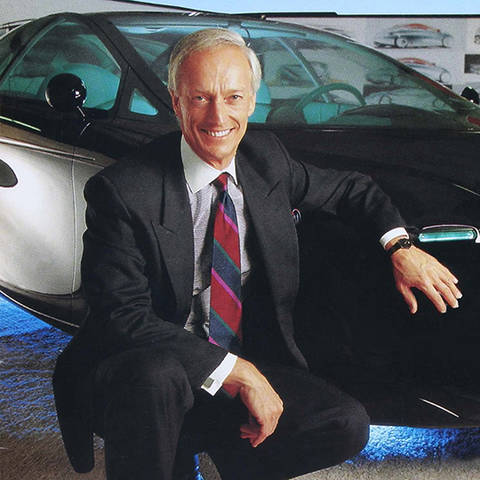

Storyboard: Jack Telnack

A Ford Man

When I was a kid, Dad used to take me to the Ford Rotunda in our hometown of Dearborn, Michigan. Being an autoholic from an early age, I remember when I first saw the 1941 Lincoln Continental on display. I was five at the time. The car was designed by Bob Gregory, who lived on Grosse Ile – the same island in the Detroit River, where I currently reside.

The Continental was unlike any design I’d seen before. It had classic proportions with a long hood, short deck, push buttons instead of door handles, and a three-quarter convertible top with no quarter window. It was an American car with European flair. It was elegant and yet seemed to gesture toward the future somehow. Frank Lloyd Wright called it “one of the most beautiful cars ever designed.”

I drew cars throughout my childhood… generally, when I was supposed to be doing homework. When I was 16, I had an opportunity to meet designers at both General Motors and Ford Design Centers. It was at Ford that Alex Tremulis, the famous designer of the Tucker, told me that my sketches were “okay” but suggested that I needed formal training and that there was only one place I could get it: ArtCenter College of Design.

That was all I needed to hear. I packed my drawing board into my chopped and channeled ’41 Mercury convertible and drove Route 66 all the way to California. It was a grand, romantic undertaking. I suppose, in a way, I really did find my dream at the end of Route 66.

ArtCenter’s Third Street Campus was the metaphorical pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. I instantly felt comfortable there. Upon graduating in 1958, I was hired by Ford and contributed to a variety of car line design programs, including the first Mustang. Ford then assigned me to Ford Australia, where I established our Asia Pacific Design Center in Melbourne. Soon after that, I was assigned to our Ford of Europe operations, where I became VP of design, with studios in London, Cologne, Germany, and Turin, Italy. Henry Ford II was the chairman of the company at the time, and I was privileged enough to have one-on-one meetings with him. To this day, my early time at Ford influenced how I would run a design team.

I’d been a Ford man all my life. I had a wife, children, and a job that provided me with security and stability. However, it was my goal and duty to stay one step ahead of the competition. That meant taking risks. The biggest risk was NOT taking them.

A designer’s role is to understand and interpret the future – which way it’s bending and turning. I felt that life was too short to simply conform; rather, it was time to redefine Ford’s future. That took guts.

A team of designers is like a team of athletes – you’ve got to secure the right players if you want to win. I’d seen recruiters from Chrysler and GM on my latter day trips to ArtCenter, and I knew we were all competing for the best students… of which, by the way, ArtCenter has plenty.

A coach calls the shots, but a coach is nothing without his team. Our team at Ford amped up the volume on aerodynamic design with the ’79 Mustang and ’83 Thunderbird. That led to the ’86 Taurus, which truly was the car that broke all the rules.

At my retirement party back in 1988, I recall a humbling moment. Amidst the revelry and reminiscing, my good friend, ArtCenter President David Brown, somehow managed to locate my original admissions letter to ArtCenter.

The initial question posed in the letter was simple: “What were my goals?” My answer: “I wanted to design for the Ford Motor Company.” To know that I accomplished the goal I set for myself all those years ago nearly brought tears to my eyes.

Jack Telnack

BS 58 Transportation Design

Retired Global VP of Design at Ford Motor Company