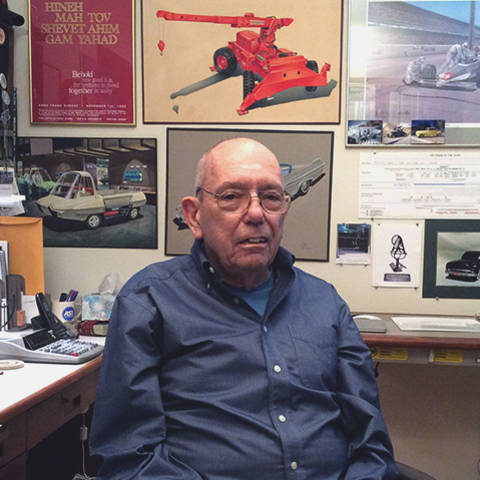

Storyboard: Gale Morris

Designing with hands that won’t do what you want them to

I grew up during of WWII. As kids, we built models of Jeeps, tanks and B-25s. Then I started making models of cars, which led to an organization known as the “Fisher Body Craftsman's Guild.” My first attempt at age 12 brought a national award of a cash scholarship in trust. Then I started playing with real cars.

My teenage years were dominated by mechanical interests. I worked a couple of summer jobs operating test versions of huge Caterpillar tractors at their proving ground, which was close to my home. I just wasn't interested in college yet. My parents suggested a visit to a place called ArtCenter, and the College turned out to be a perfect fit for me.

When I graduated ArtCenter in 1958, I called on a startup company in Oregon by the name of Tektronix (known as TEK). They had heard about Industrial Designers, but they didn't have any. We talked for two hours then they asked me to come to work the next morning. They had a vacant desk and said, “Sit here and do whatever industrial designers do.”

This new company had about 1,000 employees when I started, all local (Oregon) people. They built their first oscilloscopes with WWII surplus electronic components. TEK quickly became the world leader in building very high-end electronic test equipment.

This place was indeed a creative oasis.

I learned quickly not to ask what to do or what I should be working on. You were hired because you were perceived to have certain skills and you should be able to figure out where to apply those skills. Bringing home design awards for new products was, well, okay, but contributing new features and design ideas brought higher demand for TEK's new products. This was the real prize for our efforts. We did lots of it. The company had 24,000 employees when I took my retirement at age 50.

I’m fortunate to have a family and an education that taught me the skills and attitudes to make the most of life's opportunities AND accommodate some misfortunes along the way.

Here are mine.

I have a disability called Essential Tremor (ET). It's an inherited condition frequently confused with Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson‘s is progressive and is terminal, but my ET is neither. There are 30 million people in the USA with ET. The tremor can be with the voice, the head, feet or hands. My tremor is in my hands. Anything I do has something to do with the hands. So this “Storyboard” now begs some modification.

I simply cannot hand write anything readable. Just “use a computer” you say. The computer detects the most minute keystroke bounce so my writing is apt to look like this: h aavt hTTat is not aasoll utool to thee Probbleeem.

My history with ET is typical. It did not show until age 30. I was 24 when I graduated from ArtCenter, so I was well into my career when my shaking began.

Heavy power tools like a metal lathe or milling machine need major modifications for me to use. Hand tools also need better and longer handles because I do not have the strength now to operate them. Much of my workshop has been modified (by me) to accommodate my tremor.

I’m still a designer. I must communicate my designs via the artistic and physical skills I do have. My world now is not just visual, drawing, and rendering. I must innovate ways to work the materials that are within my limited capabilities.

How do I start a project from scratch? I don't make a drawing (my drawings are pretty bad). I might start with a chunk of walnut, a block of aluminum, or 10 pounds of our beloved dark brown modeling clay and begin to form some object which is only in my mind. Results are slower than felt-tip on vellum, but a round of mild steel in the lathe at 2000 RPM can be just as effective.

ArtCenter teaches us how to look at a problem and see a result, a thing of joy to look at, a thing of pleasure to use. We are a school of art and design and each of us work our projects to a single conclusion or crescendo. The result is not really singular, but a finished project is the blending of many answers to a problem.

Gale Morris

BS 1958 Industrial Design