Sharon Lockhart and Frances Stark

Solidarity forever: Renowned MFA alums revisit an iconic portrait

In 1997, when Sharon Lockhart, Frances Stark and Laura Owens posed in sack-dresses that collectively spelled out the “California Republic” state flag, the artists’ main intention was to present a united front for their upcoming group show at Blum & Poe in Los Angeles. But the portrait, Untitled, made by Lockhart (MFA 93 Art), also reads as a pointed declaration of independence by three women confronting a male-dominated, New York-centered art world.

“I was interested in the connection to the source, which was a Depression-era image of an American flag,” says Lockhart. “We saw the image as a positive assertion of our feminist West Coast identity as artists.” Her friend and fellow alum Frances Stark (MFA 93 Art) elaborates: “Sharon’s research has long been concerned with labor issues and the particular inspiration for this photograph was an image from an era of workers’ solidarity.”

Since making this iconic piece, Lockhart has produced photography, films and video focused on people of the Amazon, shipyard workers in Maine and other groups rarely celebrated by mainstream culture. She has spent the last couple of years immersed in a project with Polish girls residing at the Youth Center for Socio-Therapy Rudzienko outside of Warsaw. “The idea of an orphanage as a place intrigues me because, although the girls are powerless and live in an institutional setting, there is great potential in their collective voice,” says Lockhart, a CalArts faculty member.

Citing the “radical pedagogy” championed by progressive Los Angeles printmaker Sister Corita Kent and radical Polish educator Janusz Korczak, Lockhart observes, “I now realize the collaboration with Frances and Laura was very much like my current work with the girls of Rudzienko because we are working together to make a statement. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to them about what it means to be a young woman and encouraging their collective identity.”

Moving freely among mediums, Stark’s recent work has drawn on art history and literature to inform language-driven pieces brimming with digital-era conceits and complexities. It has, like Lockhart’s, also led to intergenerational creative collaboration, in Stark’s case, with her friend and “muse,” Bobby Jesus, a young man originally from outside the art world whose life story has provided inspiration for several works.

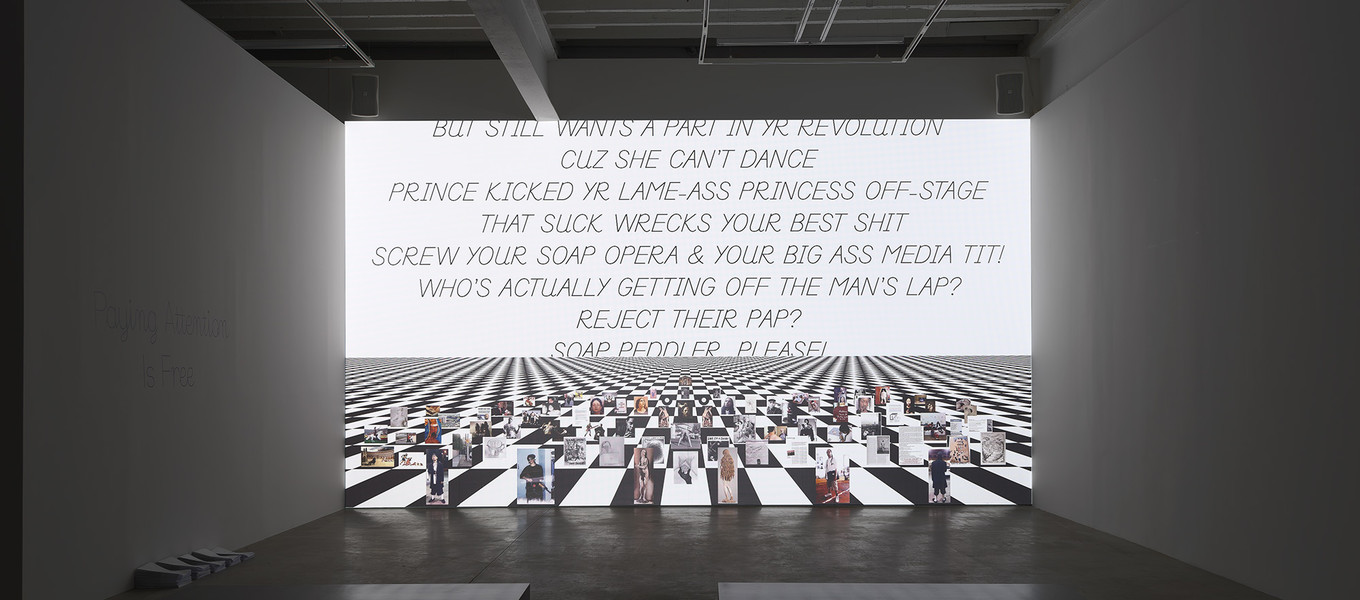

She also draws incisively on the raw material of her own life. Her humorous yet poignant 2011 text-to-animation video My Best Thing emerged from her encounters in online sex chat rooms. And her hooked rug titled How does one sustain the belief in total babes (power/recognition) which has been recognized for its debilitating effects on that person who lacks the total babe (embodiment of power/recognition) and access to the total babe by means of one’s own total foxiness/power? questions gender stereotypes. Her practice as a whole takes sharp aim at the power structures, macro and micro, that reinforce class, race and gender inequality.

The crticially acclaimed UCLA Hammer retrospective UH-OH: Frances Stark 1991–2015 presented the artist with an opportunity to reflect on her aesthetic obsessions. “Through-lines that came into distinct focus involve a joy of close-reading and the poetics, or even erotics of pedagogy,” she recalls.

Both Lockhart and Stark credit ArtCenter’s MFA Art program as a pivotal influence early in their careers. “I arrived at ArtCenter with only a vague understanding of what art was or what it could be,” said Lockhart, who singles out Mike Kelley, Tim Martin, Patti Podesta and Stephen Prina as key mentors.

Stark fondly remembers serving as the TA for the “7 Deadly Sins” screening/lecture series. “Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe chose Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, Lita Albuquerque chose Herzog’s Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Prina chose Godard’s My Life to Live, Mike Kelley screened an obscure made-for-TV film called The Baby, Patti Podesta showed Barbet Schroder’s Maîtresse,” she recalls. “The entire curriculum was perfectly seasoned with literary and philosophical concerns.”

Stark continues to explore those concerns. Deeply interested in “grappling with what constitutes an audience,” she’s now working to adapt Mozart’s The Magic Flute for the screen. “The opera will be performed by a youth orchestra we’ve assembled locally, with opera singers replaced by soloists playing the vocal melodies to accompany the animated lyrical content,” Stark said.

Why The Magic Flute? Stark, who along with Lockhart recently parted ways with USC’s Roski School of Art and Design, explains: “The choice of this particular opera is motivated by many things including my recent disenchantment with higher education and the desire to explore and celebrate a deeper belief in the emancipatory power of music, literacy and kinship over and above all of the industry preoccupation with market forces.”

Related

feature

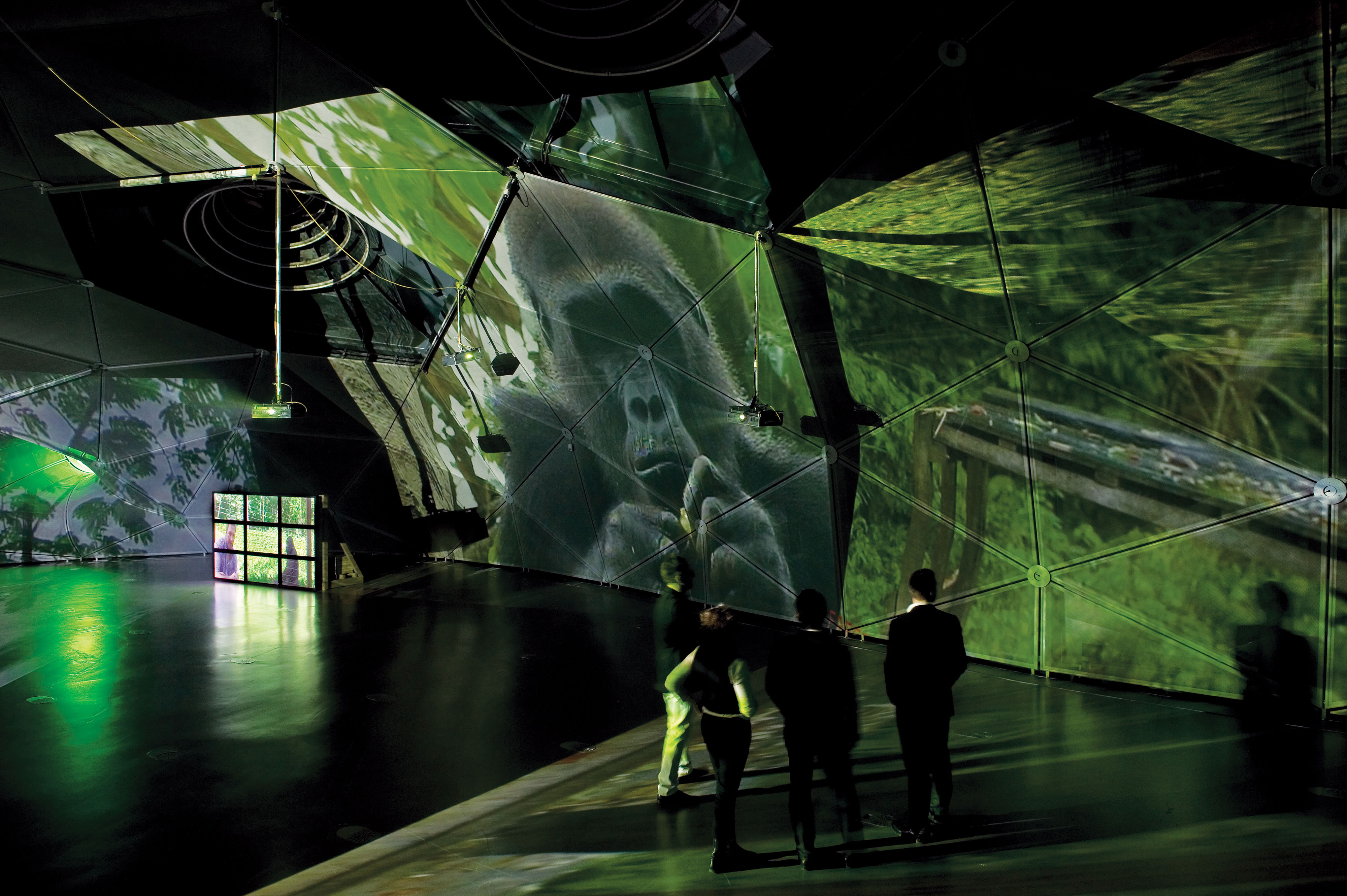

Diana Thater’s Sympathetic Imagination

October 25, 2015

feature

Sculpting Reality: Fine art student Filip Kostic deploys VR to ask big questions and create new meanings

October 12, 2016

profile